How to Renovate in New York City

Managing your renovation project through construction & beyond

The stages and timeline of construction

The general schedule for the construction or “build” phase of your NYC renovation (outlined below) should be included in your contract, complete with the duration and major milestones for each. Note that the estimated times will depend on the size of your home as well as the extent of your renovation; gut renovations of entire brownstones will take longer.

- Demolition: about 1 week

The first step is to put up protections such as zip walls to seal the demolition area. In condos and co-ops, the exterior hallways, elevators, stairs, and other common areas must also be protected.

Once these are in place, the demo work begins, involving ripping out cabinets, countertops, floors, fixtures, and any walls (for a gut renovation).

- Rough construction: about 3 to 6 weeks

This stage involves building out any new structural features and framing the walls and ceiling systems. It should not take longer than a week unless you are changing the layout.

- Plumbing, Mechanical, Electrical: 1 to 2 weeks plus at least 1 week for inspections

Once the walls are opened, it’s time for the “rough-in” work.

An electrician will run wires from the service panel to the endpoints, leaving those unattached. A plumber will also run supply and drain pipes to their respective fixtures or appliances.

Then DOB inspectors must come and either pass the work or order modifications, so the timing can vary.

Pro Tip:With more than 50,000 square feet renovated in NYC, Bolster understands how to guide New Yorkers through any renovation challenge, from navigating Landmarks to recreating pre-war details, and gives them full visibility into project milestones. "Bolster is the only renovation firm to offer a fixed-price cost up-front. Once we perform due diligence and verify the existing conditions of your property, we absorb unforeseen project costs," says Bolster's CEO and co-founder Anna Karp. Ready to start your renovation? Learn more >>

- Drywall: 1 to 4 weeks

Drywall (aka Sheetrock) is named for the fact that the “mud” mixture does not use water, making it a much faster surface than plaster (which takes a couple days to dry out). It is installed in two phases: hanging the panels by attaching them to the wood or metal studs and then finishing by taping, sanding, and skim-coating.

Some contractors will go ahead and prime the walls and ceilings now for added protection against scuffs and stains until they can be painted.

- Flooring: 1 to 2 weeks

Many types of flooring, like tile and hardwood, are typically installed before your cabinetry, though some contractors prefer to wait due to the risk of damage. Other floor types, like vinyl flooring and laminates, must be installed after the cabinets so they can be cut to precisely fit. If your hardwood floors need staining and finishing, expect to let them cure for another week.

- Cabinets/Fixtures/Surfaces: 2 to 6 weeks

Only after cabinets and plumbing fixtures are installed can measurements for countertops be taken. Fabrication for countertops can take up to one month depending on the material. If you are adding custom built-in shelving or paneling, plan to add a few extra days.

Bathroom and kitchen tiles and backsplashes are added now too.

Ultimately this phase depends on the timely delivery of materials.

- Appliances: 2 to 4 days

Once all the cabinets and countertops are in place, the appliances are positioned in place.

Lighting is usually added in a kitchen at this time too.

- Finishing details: 1 to 2 weeks

After wiping them free of dust and debris, the ceilings and walls can be painted or wallpapered. Hardware is added to kitchen cabinets and bathroom vanities. All appliances are checked to make sure they are level and connected properly. - Cleanup: 1 to 2 days

Once all the equipment has been removed, a thorough top-down cleaning should always be the final step. This includes clearing out the entire space and ventilation system of dust and debris, wiping down all surfaces and scheduling the haul-away of any dumpsters and hazardous materials.

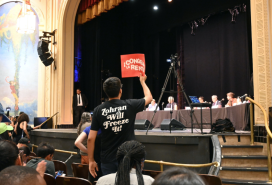

Getting along with your neighbors, board and super during your renovation

Renovations are more common than ever in New York City, so residents and building staff are used to dealing with the disruption. Your neighbors also (ought to) know they might be the ones asking for understanding at some point too. That said, construction-related skirmishes do happen. Most times these situations can be avoided––or at least mitigated.

- A well-informed neighbor is a happier one

Notify your neighbors—upstairs, downstairs, and next door—before you start work. Renovating a brownstone is no different––the sound of workers and the sight of dumpsters for months on end is undeniably an inconvenience.

If you haven’t already, introduce yourself to your neighbors in person or with a handwritten note and maybe a gift, like a bottle of wine (or noise-cancelling headphones).

Many co-op and condo buildings require written notice as part of their building alteration agreements, in which case you will need to comply. Architects often have a standard letter they pass on to clients for this purpose.

If you are drafting your own note, keep it brief and include the following:

- the start and end dates of the job

- a brief description of the work being done

- any environmental concerns, such as dust and fumes, that may come up (and that you are making all best efforts to contain those to the job site)

- assurances that the contractor has been instructed to keep common areas clean, work during authorized hours, and generally minimize disruption

- contact information in case of any concerns

- an apology for any potential inconvenience and a thank you for the neighbor’s patience

For larger jobs, it may make sense to ask permission for your architect to photograph the neighbor’s apartment so that if any damage—or claims of damage—come up, there’s a record of what the place looked like beforehand. Your board may require this.

Generally, demolition is the most difficult for neighbors due to the noise and vibrations. Fumes from paint and/or polyurethane used in floor refinishing can be disturbing as well.

As your project proceeds, keep your neighbors informed. If, for example, you know your project is going to run longer than planned, communicate that to your neighbors (as well as your board and super), along with an explanation as to why and the revised end date.

It’s also a good idea to alert your neighbors a couple days before any unusually loud or disruptive work that is about to happen so they tweak their schedule accordingly.

- Accommodate special requests if you can

Especially in a co-op or condo, some neighbors may have special requests now and then and it is important that you try and respect those. For example, a neighbor with a newborn might ask for an hour of quiet during naptime. Or someone who is recuperating from surgery may ask for a later start time in the morning or for your workers to minimize noise for a couple days.

- Check in, not out

Make a point of regularly checking in with the super and the neighbors to see if they have any questions or concerns––and to make sure the workers are being respectful and not blaring music for hours straight. This is especially important while you are vacating the premises.

And absolutely respond right away to any complaints that come your way, even if all you can do is listen to what they have to say and extend an invitation for dinner at your new digs once the work is done.

If your renovation damages adjacent apartments, be sure to act quickly. Send flowers and a note, reassuring your neighbor that you are aware of the situation and that you will see that your contractor makes repairs immediately (or whatever needs to happen to rectify the matter).

- Tips on tipping your building staff

This topic is not without its controversy; some people prefer to dole out tips to the doorman, super, porter, elevator operator, and any other building staff for all services rendered at the end of the year. But common sense suggests that giving a tip (whether $200 in cash or its equivalent, such as tickets to a game for a die-hard Yankees fan) at the outset of a renovation will keep things running smoothly. The more extensive the project, the bigger the tip.

- Keep common areas clean

This cannot be overemphasized: It is up to you to make sure your contractor and all workers ensure the dust and debris stays inside the work site, such as by taping the doors every day and wiping down their shoes so they don’t track footprints everywhere.

How to work effectively with your contractor and architect

A renovation involves lots of moving parts and it’s all too easy for things to fall through the cracks––especially when time is of the essence. Having clear communication guidelines and with your architect and contractor (or designated liaison) from the get-go is a must in staying on schedule and avoiding setbacks.

- Communicating with your contractor and architect

Before construction begins, agree with your contractor and architect how you’ll be kept in the loop. Put it in writing so everyone on your team is on the same page, noting who is the designated point person at every given stage of your project.

The contractor is generally your point person during construction. Ask for his or her preferred mode of contact, whether in person or email or by phone or text (and in that case during what hours of the day). That said, unless your architect was only hired for the design phase, you’ll want to stay in contact with that person too, most likely on a weekly basis or more frequently during specific periods (such as when custom cabinets or countertops are being fabricated).

Some experts recommend a daily check-in with the contractor (or designated foreperson), which might include meeting at the job site each morning before work begins or at the end of the day to go over what was done. Most contractors (and renovators) prefer to do this on a weekly basis, in which case you might opt for a daily email rundown, with photos if you are living elsewhere.

Be prepared to answer tons of questions throughout the project; make a point of always getting back with answers in a timely manner (the same day is best).

If you are going to be away on vacation or otherwise out of pocket, make sure to give your team a heads up so you can address anything urgent beforehand.

Sometimes it makes sense for your architect to step into the role of point person, such as when your project involves custom work (as in a kitchen redo) or whenever your contractor will need hands-on guidance in executing a design properly or help in troubleshooting any problems as they come up. Indeed architects often pay weekly visits to the job site during these build stages, and they will be the best person to provide feedback.

Later on, when the finishing touches are being added, you may prefer to deal directly with your architect or interior designer to make sure your materials and paint colors and other details are tended to.

- Staying on schedule If things ever begin to move too slowly, it’s often worth getting everyone on your team––architect, contractor, and interior designer––in one room to identify bottlenecks. A penalty clause for work that runs long will be helpful too, as you can use that as motivation to stay or get back on track.)

- Dealing with setbacks

Your first line of defense is to be proactive about checking the work. Make a point of regularly looking over the job site on your own and take notes (and photos) of any concerns that you can bring up during your scheduled check-ins.

Of course you don’t want to over-question your contractor’s work (unless it’s truly shoddy), so be tactful in how you approach these meetings, asking questions rather than passing judgment. “Does that trim look level to you?” is better than “You need to fix this trim, it looks awful.” If that gets you nowhere, you can ask your architect or interior designer to weigh in––and then be prepared to accept the consensus (it might in fact be level).

If the work is shoddy, however, you will need to address that right away and once and for all. No need pretending like it will just improve over time. Start by enlisting your architect (or interior designer) for their opinion of the contractor’s work. They have a vested interest in it being done correctly too. If there is substantiated cause for concern, it may be time to look for another contractor.

And keep in mind: You are much more likely to get quality work out of a construction crew when they enjoy working for you. That includes being responsive to your contractor’s questions and quick to make decisions (no one likes a wishy-washy client) and also friendly with all the workers.

6 common problems that can slow down or increase the cost of your renovation

Even the most experienced architects and contractors cannot anticipate every possible problem, and some things are out of their (and your) control. Here are the more typical issues that can crop up when you’re renovating;

1. Mold, asbestos, and/or lead: If these toxins are discovered (ideally in a test before work has begun), you will have to hire a qualified abatement company to safely remove them. You will also need to vacate the premises until the matter is resolved.

2. Electrical or plumbing issues: There’s simply no way for experts to see through walls, so once they are opened up a lot can happen. Pre-war co-ops and brownstones are especially prone to having outdated wiring and pipes that need updating/replacing. Regardless of the condition of your existing wiring, if you want to install powerful air conditioners or other appliances, you may need to upgrade the wiring to accommodate the heavy load they require.

3. Shoddy joists or other structural elements: These are not discoverable until the demolition phase, and then you’ll have to pay extra for reframing.

4. Missing materials: If flooring, cabinets, appliances, tiles, fixtures, and all the rest do not arrive in a timely manner, or are damaged or the wrong item, work will have to stop––often for days and weeks. Things have to be installed in a sequence, and there’s just no getting around. Order well in advance in case you have to get a replacement.

5. Contractor concerns: If you ask enough experienced renovators, you’re bound to hear tales about contractor neglect. Either they fail to supervise the project as they should or to pay their workers, who stop showing up. That’s why having a detailed schedule with payments tied to key benchmarks is essential (the carrot) as well as penalties for being late (the stick).

6. Natural disasters: Hurricanes, blizzards, and the like can happen, and there’s nothing you can do about those except wait them out (and hope they don’t cause damage to your building). Most boards will understand delays caused by these occurrences in pushing out the penalty phase accordingly.

Spend less, build faster with Bolster. "We deliver risk-free, on-time, on-budget renovations," says Bolster's CEO and co-founder Anna Karp. "We give you a fixed-priced cost up front, and absorb all unforeseen project costs after the demolition phase. Bolster--not you--is responsible for any and all surprises." Ready to start your renovation? Learn more >>

What are change orders? (and how to handle them)

Change orders are addendums to your original renovation contract that account for any additions or other deviations in the work. They can be instigated by you or your contractor or architect at any time and require your ultimate sign-off.

Change orders often arise because contractors underestimate the scope or overlook details of the project during the planning phase. (Sad to say that some contractors will deliberately omit items from their proposals for a lower bid.) Or they based their bids on incomplete drawings or erroneous designs by the architect.

Other times change orders are needed to address defects in the building that either should have been or were not able to be discovered before the work began and walls came down. This usually involves plumbing, electrical, or mechanical systems as well as foundational problems in a brownstone.

There are plenty of times when you (the client) will initiate a change order. Maybe you held off on making certain decisions or choosing materials early on, or have a change of heart about one aspect or another (like switching from a pre-fab Corian countertop to a custom marble one).

One thing to be on the lookout for: If a contractor says you need to fork over an additional $10,000 for the work to be completed, that’s not a change order but rather a cause for concern. Either they are not being cost-effective in optimizing resources or (worse) they’re taking advantage or using your money in unauthorized ways. Never pay without asking for an itemized record of labor and material costs before you agree to this demand.

Given the inevitability of changes, your contract should specify a process for submitting and approving change orders--for example, that your contractor will provide a description of what the new work will cost and how it will impact the schedule, and that you must approve in writing. (Your contract should also state whether that can be by text, email, or only pen and ink.)

Change orders will most always affect your budget and schedule. They are the reason behind the golden rule of renovating that says to plan for 30 percent more in both costs and time.

Case in point: Let’s say you planned to refinish your wood floors but then your contractor discovers they are too worn for sanding and need to be replaced. The change order causes the cost to jump from $4 to $10 a square foot, plus you’ll face a minimum of two additional weeks in selecting the material, waiting for delivery, ripping out the old flooring, and installing the new. And now you are unable to put in your kitchen cabinets or do other work until the floor is in place.

Even though your contractor should have factored this into the original estimate (by sanding an inconspicuous area, or looking at how visible the nail heads were), odds are you’d end up paying the same in the end.

Frustrating? You bet, but that’s how it goes in many renovations.

The punch list: what goes on it––and how to get your contractor to finish it

No matter how carefully and competently your renovation was planned, designed, and executed, there are bound to be items that require attention before the final sign-off and final payment. Be sure to try all the drawers and doors, look closely at the edges and finishes, and make sure everything is working the way it should.

A checklist for creating your punch list

The punch list is a tool that allows your contractor to keep track of all the bits and pieces of the job that need to be completed. By tying it to the final payment, it also serves as a financial incentive for your contractor to tie up all the loose ends.

The easiest way to organize the punch list is by room and then within each room by category––so finishes (flooring, walls, tiles, cabinetry, and countertops); doors and windows; electrical; and plumbing.

- Finishes: Make sure hardwood floors are level and properly refinished or installed if new, without any noticeable gaps between the planks (they will only get bigger and trap dust and dirt). Vinyl or laminate floors should fit snugly in corners and around cabinets, with no visible puckering anywhere.

- Walls: They can take a lot of abuse and end up with more than a reasonable amount of dings, dents, and scuff marks. Plus you’ll want to make sure the paint job is up to snuff and that any wallpaper was mounted correctly.

- Tiles: Whether in the bathroom or kitchen backsplash, tiles usually involve precise handiwork when installing, so you’ll want to make sure they are flat with consistent grout lines and patterning. Also be on the lookout for any loose or cracked tiles.

- Countertops: Your countertops should be level and match the specs; same for cabinet fronts. Check cabinet doors and drawers to make sure all are in working order––and that none of them end up banging into each other or the refrigerator due to poor design. The hardware should be tight and even, not lose or off-kilter. Same for a bathroom vanity.

- Doors and windows: Test all doors and knobs by opening and shutting and check for proper weatherstripping around exterior doors. Windows should open and shut easily, without any perceptible drafts (hard to tell if it’s summer, but still).

- Electrical: For lighting, you’ll need to turn everything on and off a few times, and then leave them on for a while. Test dimmer switches and any smart-tech functions for lighting and window shades. It’s also worth testing all the outlets by plugging things in; press the buttons on GFI outlets in the kitchen and bathrooms to ensure they trip as they are supposed to

Test all appliances too (run the dishwasher, heat the oven, ignite all burners, use the refrigerator’s water dispenser, etc.) and make sure you have all the included parts, operating manuals, and warranty materials.

- Plumbing: Make sure all fixtures (sinks, toilets, and tubs) are aligned and their surfaces are pristine. Turn on all faucets and allow them to run for a while to make sure the hot stays hot and the cold stays cold. Fill sinks all the way, then unplug and let all the water drain out, looking for any signs of leaks from the attached pipes. Do the same for the tub, making sure the overflow hole does its job (again without causing any leaks to the room below). Showerheads should have ample power, and any smart fittings should do as they are designed.

The final walk-through

Once your punch list is complete, schedule a time to review the work and any outstanding issues with your contractor, who may be able to fix them on the spot or arrange a time to come back (asap). It’s also entirely possible that you will discover new items for the punch list at this time.

Tips for getting your punch list done

The worst thing you can do is wait until the end of your project to hand over your list. By that time, your contractor probably has another project on the schedule and is expected elsewhere.

Instead, start itemizing things that need to be taken care of during the last 30 percent of the job––or better yet, tie the second-to-last installment payment to completing these items rather than waiting for the final one. This way the final punch list should be fairly limited too.

Barring any backordered items, your contractor should be able to return and fix everything in a few days, especially if you’ve been whittling down the list all along.

The final items on your punch list are always the toughest to get completed. Most experts recommend withholding a small percentage of the contractor's price––usually around 10 percent––until all items are finished to your satisfaction.

For smaller jobs, you may need more of an incentive for the contractor to tackle everything. In those cases you could withhold 15 percent and then pay that out in two installments while the punch list is being completed. This is a fairly standard practice in the industry and should be set out in the 'hold-back' provision in your contract.

If you’ve already paid your general contractor in full and still have a few lingering punch items, you may have to be persistent by calling or sending emails until you get a response. Sometimes a personal note with a few kind pleas for help will achieve quicker results than expressing your frustration harshly.

But if all else fails, you can play the “reference” card, since client referrals are contractor’s bread and butter.

Before you make a final payment, get a lien waiver Contractors and subcontractors can file liens if they haven’t been paid for completed work, even if it’s not your fault. Having a lien on your property can wreak havoc when you are selling it, causing unexpected delays (and possibly scaring off potential buyers). It can also prevent you from refinancing or prevent a buyer from getting a mortgage to buy your place.

Ask your contractor to provide lien waivers from all subcontractors and suppliers stating they have been paid and giving up the right to file a future lien. Be sure to do this before final payment.

When do you need a new certificate of occupancy—and how do you get one?

If you're doing significant renovations or purchasing a fixer-upper with the intention of launching into extensive work, you may need to update the certificate of occupancy (or C of O) in addition to getting all the requisite permits. But that’s not always the case.

Simply put, a C of O is a document that lays out a building's legal use and occupancy. In a residential building, that includes how many bedrooms or exits are allowed at that address. Without an up-to-date C of O, no one can legally occupy a building, so you run the risk of the city issuing a vacate order. It can also complicate matters when you try and sell your property. Usually any C of O problem will surface in the title search, and a potential buyer may walk away if they think the situation will take too long to correct.

You need a new Certificate of Occupancy if you’re:

- Subdividing an apartment or even installing a floor-to-ceiling partition to create an additional bedroom

- Turning a two- or three-family building into a single-family residence (or vice versa)

- Converting a space previously designated for laundry or storage to increase the number of units

- Modifying the layout of stairs, corridors, lobbies, and fire escapes that would affect exits

Combining apartments? You may not need a new Certificate of Occupancy

Interestingly, you don’t need a new C of O if you’re combining apartments, so long as you meet certain restrictions:

- The apartments being joined are on the same floor or adjacent floors using interior access stairs that connect no more than two stories

- Each unit retains existing exits (or egress) from all stories of the building, such as stairs, corridors, passageways, fire escapes, or lobby

- The combined unit will have the same or fewer zoned rooms (meaning you are not combining two two-bedroom apartments into a five-bedroom unit)

- Each new habitable room is compliant with natural light and air requirements

- The second kitchen is eliminated and the plumbing connections capped (unless used for a bathroom or other space)

Note that when combining apartments in a condo building, you must also obtain a new tentative tax lot number from the Department of Finance.

How to get a new Certificate of Occupancy

To get a new C of O, your architect must include this request in the plans that are submitted to the DOB before work begins. Then, once you’ve passed inspections, received all appropriate city approvals, and paid any outstanding fees, the DOB may either issue a new/amended C of O, or a Letter of Completion if the scope of work didn’t require a change to the existing C of O. This document will put the final stamp of approval on your renovation and is usually issued within a day or two.

How to get problems fixed after your renovation is done

Even if you didn't lay the groundwork early on by negotiating a warranty for your contractor’s work in the contract, you are entitled to a resolution. And should a problem not end up not being your contractor’s responsibility, getting his or her feedback can be helpful in figuring out the best way to fix it.

Most common post-renovation issues

Leaky pipes (causing damage to the floor below), defective appliances, non-working electrical outlets, malfunctioning radiant heat units, cracks in the walls and ceilings, doors or cabinet fronts that won’t shut properly, faulty windows, warped floors––these are just some of the more typical issues that can arise weeks or months or even years after sign-off. In a brownstone the list also includes problems with the foundation, mechanicals (boiler and hot-water heater), and the roof.

Just because there’s a post-renovation problem doesn’t mean the contractor is to blame. Usually some investigation is needed in identifying the cause, and there are multiple steps along the way––from initial spec to manufacturing of the material and installation––where errors can occur.

For example, your floor might be warping from defective materials or installation (usually by not having the proper substrate), or from excess humidity in the home from a faulty HVAC system.

Problems also occur due to improper use and general wear and tear (such as damage caused by routinely putting a hot pot on your Silestone countertop).

How to get things fixed

Whether your floor is buckling or water is leaking into the bathroom when you shower, there’s an escalating series of actions you can take to get things resolved.

- Asking nicely but firmly Start by trying to appeal to your contractor’s own sense of obligation. Calling their business or showing up in person and showing proof of the problem is sometimes enough to get a reputable contractor to come back and investigate the situation.

- Social Media These days, social media is a powerful forum for voicing complaints about a business. You can comment on the contractor’s website or Facebook page, for example, being sure to strike an appropriate tone (e.g., don’t be belligerent and provide facts to bolster your complaint).

- Professional Complaints You can file complaints through the New York State Divison of Consumer Protection as well as the Better Business Bureau.

So long as your contractor is licensed, you can file a complaint with New York City’s consumer affairs department, which upon review will contact the business and begin mediation. The department can require the contractor to pay restitution or fix or finish the job. It can also file charges against the business and seek a decision from an administrative law judge, who can order a business to pay restitution, issue a fine, or revoke the contractor’s license.

If the business doesn’t have the resources to pay you, the department can tap into its home improvement contractor trust fund to award you up to $25,000.

Some licensed contractors purchase a surety bond from their insurance agent in case of client disputes. If you file a claim, the bond policy pays you to compensate for your losses. (And then the insurance company goes after the contractor.) So you can start by contacting your contractor’s company.

- Going (or threatening to go) to court

Under New York law, you can sue a contractor for construction issues within three years of the contract date (and architects within six years), even if you agreed to a one-year warranty in the contract.

If you've got a faulty appliance or fixture problem on your hands, it’s typically the manufacturer’s responsibility to replace it, provided you are still within the warranty period. But even if the window manufacturer puts in a new window for free, they won’t pay for the labor involved in ripping out the old one and repairing any damage to the inside. And if you purchased the appliance or fixture through your contractor or architect (they specified it, ordered it, and made a commission), then your contractor or architect should handle any repair or replacement.If you have suffered financial damages (say, you had to pay for repairs to your downstairs neighbor’s property), you can pursue litigation. This is usually your only option for unlicensed contractors too.

But first, under New York’s right-to-remedy law, you are required to notify the contractor of any perceived defects in writing and provide that person an opportunity to remedy them.

For losses under $5,000, you can sue in small claims court without a lawyer. Otherwise you’ll have to find a lawyer willing to take on your case––meaning you will need to have a good shot of establishing liability and the recovery amount is lucrative enough to justify paying attorneys fees.

No matter which avenue you take, the more detailed your “evidence” is, the better the odds of a favorable outcome. Keep a paper trail of the work before, during, and after the project. Print out all emails and document all texts and phone calls with the dates and discussion points. Take photos of every stage. Post-project, send letters with your concerns to the contractor via certified mail.