First rent: How the rent can be hiked on newly combined stabilized apartments

- It's a strategy that allows landlords to raise rents well above stabilized limits

- These 'Frankenstein' units still have limited rent increases and automatic lease renewals

First rent refers to the rent a landlord can charge for a newly configured apartment with no previous rental history.

iStock

If you find a listing for a large apartment in New York City that is the result of combining two rent-stabilized apartments—you may notice the rent for the combination apartment is proportionally higher than other rent-stabilized units in the building. That's because the landlord has set a "first rent," and it refers to the much higher amount a landlord can charge for a newly combined apartment that's never been on the market before.

However, the apartment will continue to be subject to the rules of rent stabilization: limited rent increases and automatic lease renewals.

[Editor's note: An earlier version of this article was published in September 2022. We are presenting it again with updated information for May 2023.]

Possible changes for ‘first rent’

Combining or changing the configuration of units (splitting a larger apartment into two or incorporating a large amount of common space like a hallway into an apartment) is a way for landlords with rent-stabilized apartments to increase the rent they can generate from a building.

Sometimes these units are referred to as "Frankenstein" apartments—because they are pieced together from neighboring units. This strategy of apartment reconfiguration is one of the few routes available to landlords to significantly raise the rent of a stabilized apartment.

The Division of Housing and Community Renewal proposed eliminating the practice of first rent with an amendment to the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act. One of the main goals of that landmark legislation, passed in 2019, was to make it more difficult for landlords to cycle affordable apartments out of stabilization. Closing this loophole could put an end to big rent increases for combined or significantly altered units. The public review period for the amendment ended last year.

"The next step is for DHCR to simply publish the amendments. I don't know why there has been such a long delay," says Edward Josephson, supervisor at Legal Aid’s Law Reform Unit.

Combining apartments to increase the rent

In the meantime, creating a combination apartment continues to be one way to hike the rent of a stabilized unit. There is no cap on what that new rent is, so the apartment can be rented out at whatever rate the landlord chooses.

That rent becomes the legal rent and any renewal would only raise the rent in line with annual increases set by the Rent Guidelines Board. As a tenant, you have all the protections offered to tenants in rent-stabilized apartments, including automatic lease renewals.

If you are renting in an apartment where the landlord believes they may be able to combine it or change its configuration to get a "first rent" from a new tenant, this may present an opportunity to negotiate a buyout from your landlord. These deals happen when a landlord can increase the rent substantially by buying you out of your lease and getting you to move out.

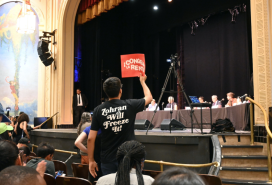

This issue was addressed recently during Brick Underground's Office Hours—a live forum for your questions. To find out about our next event, subscribe to our newsletter.

Why apartments might be sitting empty

When the law changed in 2019, there was a lot of talk of landlords warehousing apartments in order to combine neighboring units and increase rents. Noah Rosenblatt, co-founder and CEO of real estate analytics firm UrbanDigs, has previously said that thousands of rent-stabilized apartments are sitting empty while landlords consider their options for these apartments.

It may be hard to fathom, but from a landlord’s point of view, it’s very difficult to move a tenant out of a rent-stabilized apartment and it could be decades before it is vacated, so some landlords would prefer the apartments sit empty for now and in hopes that legislation shifts in their favor.

Josephson says the whole point of the Housing Stability and Tenant Protections Act was to take away the incentives for landlords to evict tenants. “If you’re a tenant and you live next to a vacant unit, the landlord has a big incentive to evict you so that they can combine the unit,” he says. That’s why Legal Aid supports the changes.

“DHCR’s new regulations are in harmony with the purpose of the HSPTA, which is to disincentivize landlords from evicting people,” Josephson says.

The changes face opposition

Landlords will inevitably fight any changes. Attorney James Marino, a partner at Kucker Marino Winiarsky & Bittens, says the proposed changes could also result in “a dearth of affordable larger apartments.” That is, landlords will lose the incentive to create larger apartments in older prewar rental buildings in popular neighborhoods like the Upper West Side and East Village, leaving families limited to expensive luxury developments in gentrifying neighborhoods.

Tenant advocates say this argument doesn’t hold water. There’s nothing to prevent landlords from creating larger apartments if there’s a market for it. “It’s just that under the new system one plus one equals two and under the old system one plus one used to equal 10—and that didn’t make any sense,” Josephson says.

Cea Weaver, a tenant activist at Housing Justice for All, says the new regulations are common sense. "[They] will keep housing stable for families in the face of rapid gentrification in NYC," she says.

You Might Also Like