The biggest moments in NYC's transit history

Construction of a subway tunnel at 42nd Street, between 5th and 6th Avenue, 1901. Via the NYPL Digital Collections.

In his recent Netflix special, New York Story, comedian Colin Quinn deemed the New York City subway a "misery creator," noting that after a few months of contending with delays, crowding, and all the other woes that come with regular use of our quirky transit system, even the most patient Midwestern transplant will eventually snap.

Anyone who's been stalled in a tunnel or crammed into the armpits of strangers a few times will agree. But for all our complaining about the MTA—perhaps a New Yorker's favorite pastime, or at least one of them—the city's public transportation network is still a staggering feat of infrastructure, with a back story as full of highs and lows as any great drama. Here, some of the most fascinating and pivotal moments in NYC's transit history.

The city transitions from horse-drawn carriages to mechanized public transit

According to the New York City Transit Museum, beginning in the 1820s, the first form of public transit in NYC was by horse-and-buggy. Horse-drawn omnibuses and cars could transport small groups of people along fixed routes, but the industry was unregulated, resulting in frequent traffic jams and accidents. Housing and feeding the horses amounted to no small expense, either, and the animals often had short-lived careers.

The legacy of this era of transit can be seen in carriage houses, now coveted city properties that were once used as stables, as well as in a body of water with an odd name: Dead Horse Bay. In a Brick interview, the creators of the journal Underwater New York explained that when the city's horses died, they were sent to glue factories by Coney Island Creek, where the animals' skeletal remains can still be found on the beach.

This inefficient industry began to be phased out in the late 1880s, with the advent of cable cars, trolleys, and buses. Per the history buffs and podcasters the Bowery Boys, the city's first cable car system debuted in 1883, using steam power to traverse the Brooklyn Bridge. A few years later, the city began establishing electric-powered cable car lines in Manhattan; because horse-drawn carriages were still in use at the time, there were frequent traffic tangles between machines and animals.

Union Square was a particularly treacherous area, with a "Dead Man's Curve" which trolleys sped around, risking life and limb of passengers and pedestrians. Nevertheless, the system expanded, and the city bid farewell to horse buggies, at which point the electric trolley enjoyed a brief heyday as the dominant form of public transit in NYC.

By the 1930s, however, the city began ending trolley operations in favor of using buses at the street level. Gothamist suggests that the reason for this transition wasn't that buses were more efficient—streetcars were (and are) considered clean and quick—but that General Motors took over and then quashed the trolley line operators to make way for its own product.

Streetcars might be making a comeback, though: The city is currently exploring possible routes for the Brooklyn-Queens Connector, a proposed streetcar that would run along the East River waterfront in Brooklyn and Queens. While some welcome the prospect of quicker connections between the boroughs, others see the project as a colossal waste of money. The Village Voice criticized the plan, calling out the idea that the $2.5 billion streetcar line would eventually pay for itself as "untenably optimistic."

Perhaps it could make use of the remnants of the trolley system that can be found throughout the city: Forgotten New York has several photos of old stations, noting that the last one brought passengers from Queens to Roosevelt Island until its closure in 1957.

The subway makes it debut and quickly expands

Upper East Siders who waited decades for three new Second Avenue subway stations to open might be aggravated to hear that the very first subway line in NYC opened in 1904, after a mere four years of contruction. And according to another article from the Bowery Boys, that line spanned an impressive distance, from City Hall to Harlem.

The efficiency with which this first, 9.1-mile leg of the system was constructed by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) was partly due to the financial abundance the city was undergoing during the Gilded Age, an era from roughly 1870 to 1910, when the city also undertook other expensive infrastructure projects, including building the Brooklyn Bridge, erected skyscrapers, and opened Central Park.

It may have also been fueled by a competitive spirit, as Boston had already opened its own underground transit system. As Doug Most, author of The Race Underground, told the Bowery Boys, "New Yorkers were not happy to see that little podunk city to the north making so much progress."

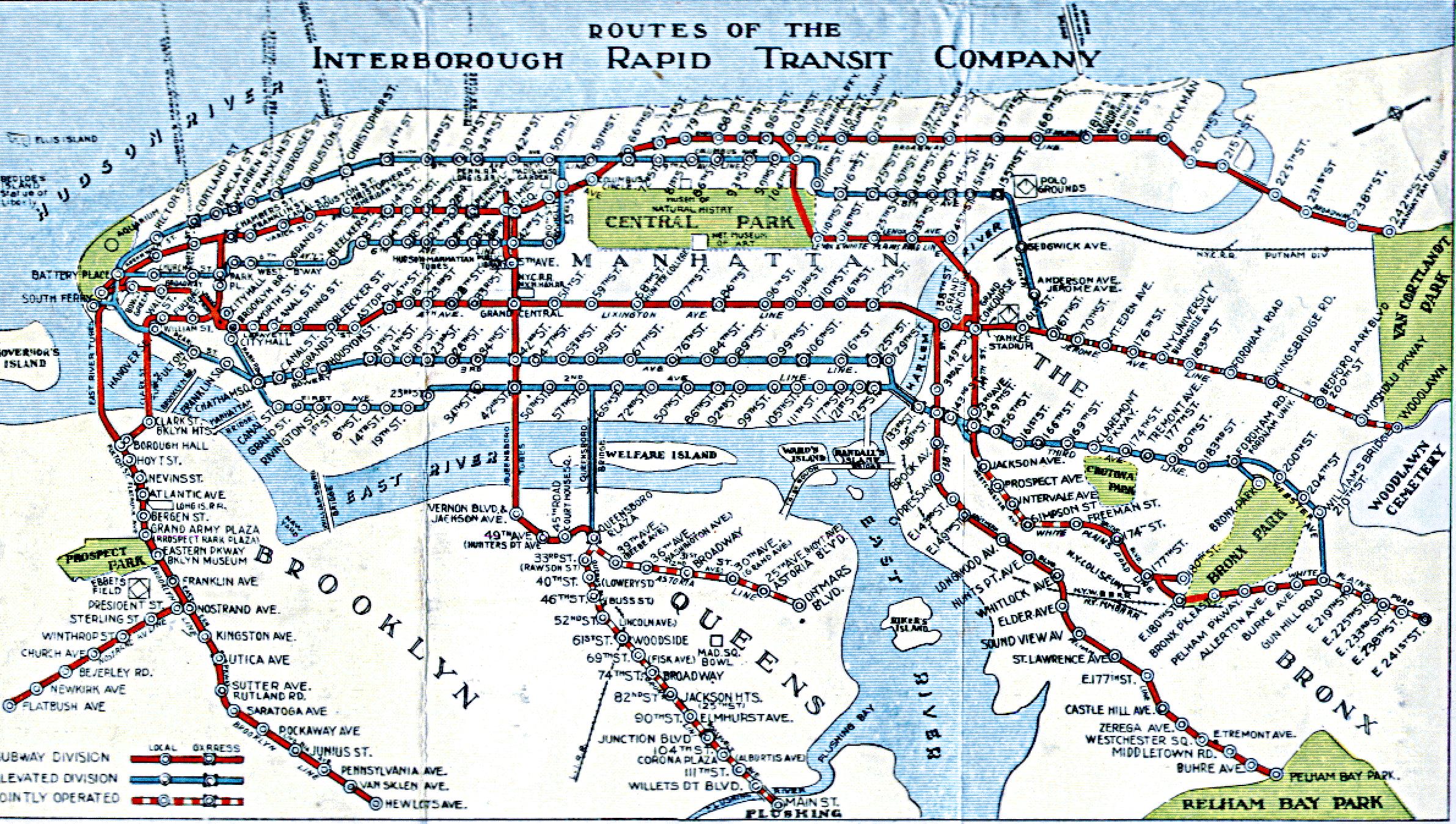

Per the Transit Museum, the IRT carried 100,000 passengers on its first day, and could travel at speeds of up to 40 miles per hour, which made the pace of trolleys and elevated trains seem plodding by comparison. The map below shows the IRT system as of 1939.

Soon, New Yorkers were clamoring for more subway lines, and by 1905, the city Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners promised another 19 lines, writes PBS. But the lion's share of subway construction took place after 1913, with the signing of the Dual Contracts, official documentation signed between the city and the private rail companies. This split new line development between the IRT and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT), which previously had operated streetcars and elevated trains thoughout the borough.

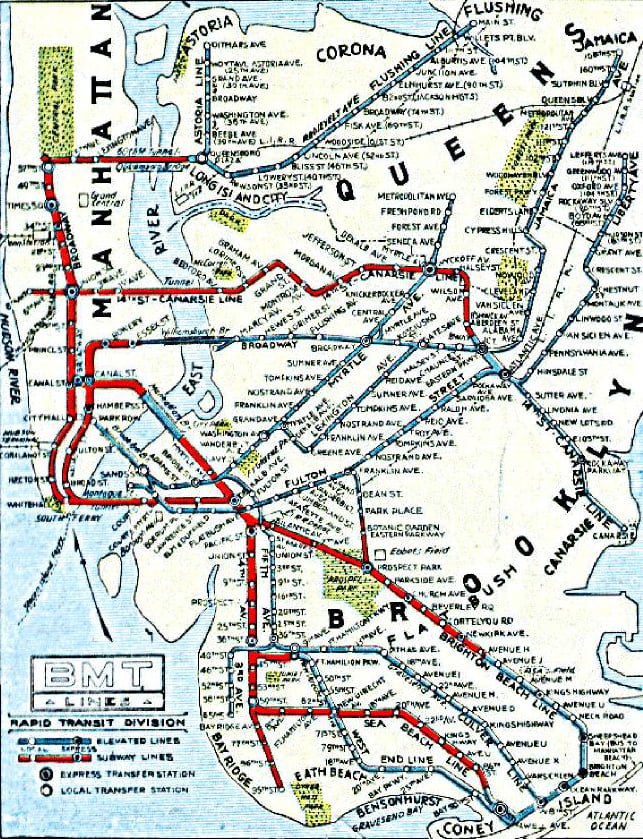

Below, a map of the BMT system from 1939:

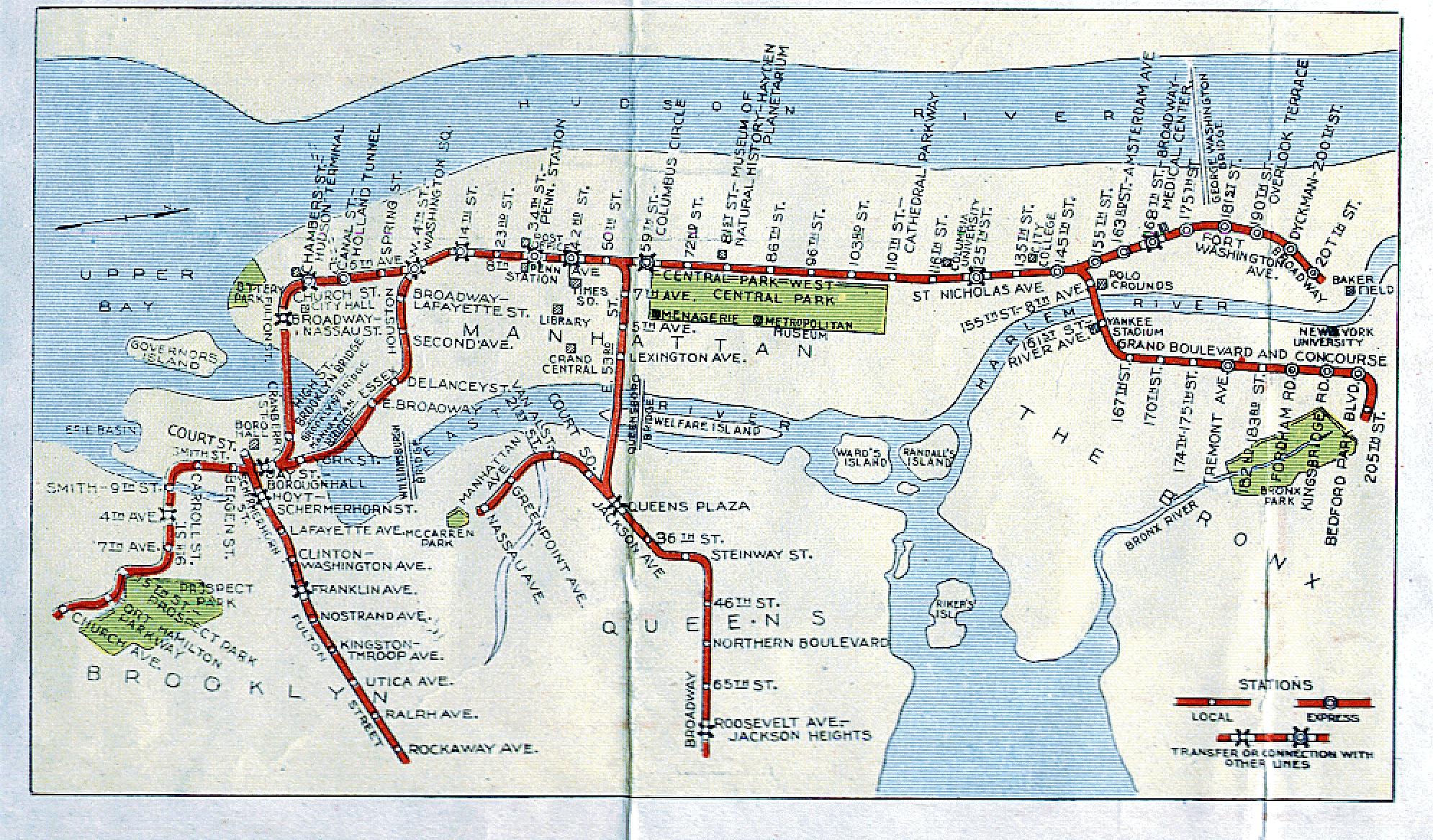

The MTA explains that the IRT oversaw the extension of new lines to the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens, while the BRT, which later became the BMT in the wake of financial troubles, linked Brooklyn and Manhattan. In 1932, the city decided to get into the subway business, opening the Independent Rapid Transit Railroad (IND), whose first effort was what the Eighth Avenue line, running from 207th Street to Chambers Street. See that company's map below:

The city grows, along with the subway

The construction of new subway lines and stations was instrumental in NYC's expansion--and seems to have had a snowball effect. Development flourished along the new lines, with New Yorkers quickly catching onto the convenience of the new form of transit. An article published in Century Magazine in 1902 observes, "Morning and night the hordes of clerks and stenographers and business men who fill the offices of down-town New York have poured across Newspaper Row and City Hall Park with scarcely a glance at the labor progressing underfoot that is going to bring them so many minutes nearer their work in the morning, and at night so many minutes nearer their play."

This flurry of new construction, however, quickly led to the overcrowding and delays we know so well today, which then necessitated the construction of new lines. NYCSubway explains that by the time the IND was established in 1920, the subway lines were already "victims of their own success," overburdened by passengers.

Clearly, locals were clamoring for more options: A New York Times article from 1932 recounts the glee that accompanied the debut of the Eighth Avenue Line, which ran from Chambers Street to 207th Street. The article notes that "Subway stations have been located with respect to the density of population in connection with running distances between stops," and quotes business owners in the area who were "unanimous in their belief that its opening marked the beginning of better business conditions in that territory."

Decisions about where new subway lines were established depended on a variety of factors. What is now the 7 line, for instance, was extended to Flushing by the IRT to bring visitors to the 1939 World's Fair. And by 1925, Union Square was already so congested with transferring commuters that then-Mayor John Hylan suggested extending what's now the L train line to 8th Avenue.

Amid all the subway construction of the early 20th century, there were NYC neighborhoods left transit deserts, despite the wishes of the mayor. NYCSubway explains that Hylan set forth a goal that anyone living in Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens would be within half a mile of a subway station, a lofty aim that was dead-ended by politics and money. One NYC official, for instance, didn't want elevated trains in the outer boroughs, which he claimed would negatively impact home values. And when the Depression hit in the 1930s, financial strain curtailed development.

The separate subway companies are combined—and elevated trains begin to disappear

Despite the IRT and BMT's success in expanding rapid transit across the city, by the late 1930s, the two private companies were struggling financially. At this time, subway fare was only five cents, which placed a great deal of stress on IRT and BMT coffers in the wake of the inflation that followed World War 1. This, compounded by the scarcity of the Great Depression, meant the companies could barely stay afloat.

In 1940, the IND, then operated by NYC's Board of Transportation, took over the other two failing companies, bringing the city's entire subway system under the authority of a single agency. In 1953, according to Quartz, this agency became the New York City Transportation Authority, and later the MTA that we all know and love to complain about today.

At the time, not everyone was thrilled about the transit changes that came out of unification. NYCSubway.org explains how the the city began eliminating certain lines it deemed inefficient too costly after the deal was finalized; this included a number of elevated train lines, which ran along several avenues in Manhattan. (As the subway, speedier than elevated rail, expanded, the els became obsolete, and the city feared it would soon be operating them at a loss.)

A history professor tells CityLab these were "loud, dirty, messy, and slow," increasingly unattractive options as subway service expanded. Among them was a Second Avenue El that used to run from City Hall all the way to the Bronx, and as we all know, Upper East Siders had been waiting since then for a replacement.

There remain differences between the subway lines, depending on which company used to operate them. The former IRT lines are the numbered trains, while the ex-BMT and IND lines have letters; the IRT trains are also slightly narrower than the others. And as with the trolley system, there are remnants of the decomissioned elevated trains scattered across the boroughs, which Forgotten New York catalogues here.

The subway falls on hard times

In his stand-up special, Colin Quinn recalls the dark days of NYC, when the MTA warned subway passengers that it was "chain-snatching season"; crime was so rampant that everyone, even the transit police, he says, were afraid to enter the last car of the train, and a lawless, every-passenger-for-himself vibe prevailed.

Second Avenue Sagas looks back at how the city maintained the subway's five cent fare, even when it clearly wasn't enough to maintain a system that was seeing more and more passengers in the wake of World War 2. The 1950s saw extensive closures of elevated trains, and the city adopted a policy of "deferred maintenance"—that is, putting off repairs and upgrades to the infrastructure.

And when NYC plunged into fiscal crisis in the 1970s, the system truly went downhill, with more elevated lines being shut down but never replaced. Then came the era of crime and vandalism that would plague the subway for years: The New York Daily News has a photographic retrospective of these dark days, documenting robberies and assaults, as well as the graffiti and trash-riddled train cars.

On NYCSubway, Mark Feinman writes, "conditions were so deplorable that it was amazing that trains even ran." The MTA initiated a series of fare hikes in an attempt to generate funds for improvements, but, Feinman continues, "with this fare hike, ridership declined, and this vicious cycle of fare hike/reduced ridership would repeat itself several times in the 1970s."

The much needed maintenance wouldn't come for another decade.

The first branch of the Second Avenue subway debuts

The subway began to recover from its decline in the 1980s, thanks to New Yorkers voting in 1979 for a $500 million bond to fund the desperately needed improvements, Feinman writes. The system was so degraded, though, that it would take until the 1990s for all the lines to even get air-conditioning. No wonder, then, that construction of an entirely new line wasn't given top priority.

But finally, at the beginning of this year, the first three stops of the long-awaited Second Avenue Subway finally opened, some much-needed good news given that Gothamist recently reported that subway service in general is, once again, getting worse.

January 1st, though, was a hopeful, happy day for NYC transit. The stations at East 72nd, 86th, and 96th Streets—the first leg of a line that has been talked about since the 1920s—opened to the public, bedecked with impressive public art and welcomed especially by residents of Yorkville, long a transit desert.

Nick Paumgarten of the New Yorker was present for the opening of the station at 96th Street, and reported something highly unusual: New Yorker being gleeful about public transportation. "The mood aboard was giddy," he writes. "Rounds of cheers greeted the routine recorded announcement (“Stand clear of the closing doors, please”), the first hint of movement (Euro-smooth, not lurching), and, finally, the remarks over the public-address system from Governor Cuomo, who was up front in the engineer’s booth (“Rest assured, I am not driving the train”)."

Sure, our complicated, and sometimes crumbling, transit infrastructure makes us all miserable sometimes, but it's refreshing to see that hardened New Yorkers still have the capacity for wonder at the system that moves us all.

You Might Also Like