Stop blaming the hipsters: Here's how gentrification really happens (and what you can do about it)

A scene from gentrifying Harlem.

iStock

Jeremiah Moss writes in his new book Vanishing New York: How a Great City Lost Its Soul that when he first arrived in New York City in 1993, the city was "at the beginning of its end." Moss attributes what he sees as New York’s untimely death to hyper-gentrification, the same "unstoppable virus" besieging other cities, from San Francisco to Shanghai.

Longtime New Yorkers have seen innumerable neighbors displaced and independent businesses shuttered, and watched as the ranks of the city's homeless swelled to over 60,000. The changes are easy to see, but it’s not always obvious where they originated.

Sometimes the blame falls on individuals, and not even developers—we're talking about the hipsters, the yuppies, the "creatives," arriving in neighborhoods with no awareness of local history or concern for how their arrival might be linked to people being priced out.

Take the recent controversy over a "boozy sandwich shop" opened recently by a Canadian transplant in Crown Heights. Its owner, Becca Brennan, hawked 40-ounce bottles of rose and promoted the business's “bullet hole-ridden wall” as a funny reminder of the neighborhood's violent recent history. At an ensuing protest of the bar, a man was photographed carrying a sign that read, "THIS IS WHAT GENTRIFICATION LOOKS LIKE!"

[Editor's note: This story was first published in September 2017. We are presenting it again here as our weekly In Case You Missed It pick.]

No doubt Brennan's approach was tone deaf, but rather than being a sower of gentrification, she is more like a symptom of it. The roots of the phenomenon reach way back through history and public policy, Moss and other close observers of New York’s transformation say, and the transplants who arrive in a working-class neighborhood selling $15 cocktails are just one step in a lengthy process.

In a 2015 study on gentrification and displacement, UCLA and Berkeley researchers write that there are three factors driving neighborhood change: "movement of people, public policies and investments, and flows of private capital." They continue, "These influences are by no means mutually exclusive—in fact they are very much mutually dependent."

Moses Gates, director of community planning and design at the Regional Plan Association, says that when it comes to gentrification, “The general argument that you run into is over whether city policies drive demand through upzoning," that is, allowing the construction of taller buildings, "or if they are reacting to demand and, without new development, the situation would be worse. That is where most of the tension lies. I think both and neither are true—it’s all part of the story.”

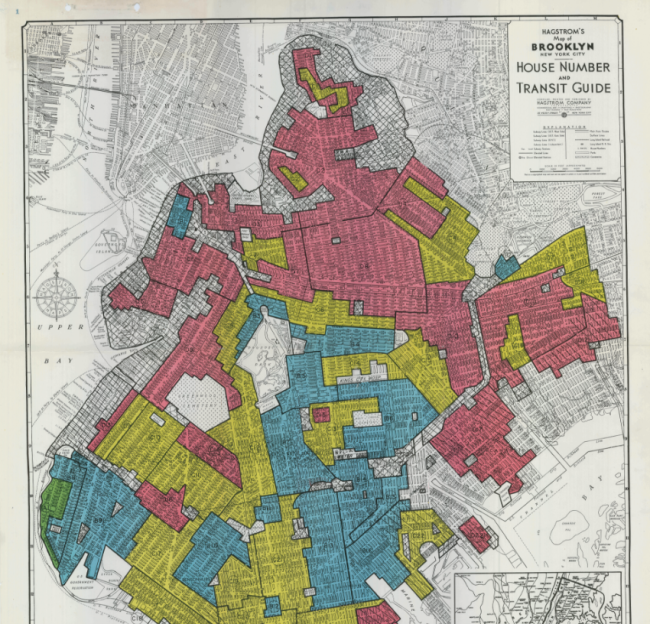

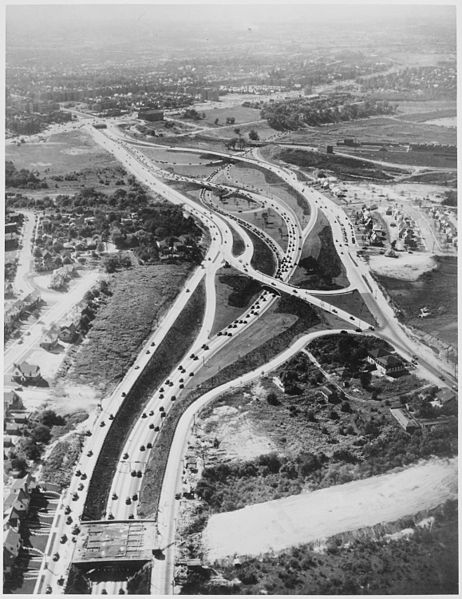

Looking west along the Grand Central Parkway from Kew Gardens in 1946. A combination of whites-only home ownership support programs and highway building propelled white flight and the suburbanization of the U.S. Department of State/Wikimedia

The role of public policy and private investment

Celia Weaver, research director at the activist group New York Communities for Change, says gentrification has roots in public policy.

"When capital flows into a neighborhood, people are displaced. Bankers and landlords speculate on low-cost neighborhoods with the assumption that they’re going to be able to raise the rent and in order to make that work, they then have to," she says.

Banks make loans to developers, and investors fund the purchase of buildings, with the agreement that the loans will be repaid at certain rates, or that they'll get a certain return on investment. Baked into these agreements often is the notion that tenants and apartment buyers will soon be paying much more than they do now. Without the building owners following through, i.e. renting and selling at new, higher rates, they are liable to fall behind on their payments.

Thus, Weaver says, "Bankers speculating on low-income housing need to create a displacement crisis so they can bring in new people, in order to make their gamble work."

Speculation is easier when it's supported and encouraged by politicians. Moss sees the recent spate of changes that have come to New York—the influx of wealth, exponentially increasing housing costs, the disappearance of independent businesses, and the displacement of longtime locals—as originating in the 1970s, when city leadership began implementing policies favoring privatization and deregulation.

"Under Mayor Ed Koch, City Hall’s goal became to recreate New York, making it friendly to big business, tourists, real estate developers, and upscale professionals," he writes. "The city brought in big real estate developers and corporations with generous tax abatements and other government subsidies. Public money for the poor was rerouted to the rich."

The wave of gentrification that resulted from these policies stalled during the recession of the late 1980s, he continues, but returned under the tenure of Mayor Bloomberg. In 2003, the billionaire businessman described NYC as a "luxury product" that should brand itself like a private company, an outlook reflected in his administration’s approach to rezoning.

"The rules were changed for thousands of city blocks," writes Moss. The changes prohibited building taller in certain areas, most of them majority white and high-income, while encouraging it in others.

Weaver notes that the Bloomberg administration "didn't increase development capacity all that much. What it did," she says, "was protect white, homeowner voters, while putting renter neighborhoods in the line of fire" for being displaced.

Another far-reaching policy change was Bloomberg’s model of affordable housing.

"'Affordable' really means income-targeted, because the model is mixed-income developments where most of the building is unaffordable to the neighborhood and in fact above the market rate of that neighborhood, to create a planned new market," Weaver says. The centerpiece of Mayor de Blasio's affordable housing plan is rezoning certain low-income neighborhoods and requiring that developers include a certain portion of income-restricted housing in each new building. In other words, he is continuing the Bloomberg approach, albeit with greater requirements for the amount of below-market apartments they must set aside.

Weaver points to new development in East New York as one example of how even the addition of ostensibly "affordable" housing can further the pushing out of a neighborhood's existing residents.

"A lot of the affordable housing in East New York is for renters earning 80 percent [area median income], which is well above the neighborhood’s median income," she says. The combination of upzoning, allowing mostly market-rate housing in the new buildings, and setting aside the remaining apartments for people making more than what's typical in the neighborhood, she says, "creates a higher-level housing market at a scale that’s unprecedented."

Compounding the problem is that as housing costs have risen out of reach to many lower-income New Yorkers, the number of rent-regulated units has diminished. Rent stabilization was created in the 1960s in response to growing housing scarcity and complaints of rising prices, and the system protected many renters from being rapidly priced out of their homes.

The regulation is still with us. In fact, nearly half of all rental apartments in the city are still rent-stabilized.

But beginning with a 1994 City Council vote that allowed landlords to deregulate apartments once the rent hit $2,000 (today it's $2,700), legislators created a series of escape hatches in the rent regulations that enable owners to take units out of stabilization. Under the setup that exists now, landlords stand to make the biggest profits if they can compel their rent-stabilized tenants to leave. Pro Publica reports that of the 860,000 apartments that were stabilized in the mid-'90s, almost 250,000 have become market rate in the intervening two decades.

Children of the suburbs return to the cities

Benjamin Grant, urban design policy director at the San Francisco-based think tank SPUR, says that in order to understand hyper-gentrification, you have to go back further than the 1970s.

It began with the suburbanization of the United States during the mid-20th century, he says, which was supported by federal policies that underwrote mortgages, but only for white people, and subsidized the building of interstate highways.

"Center cities were hugely abandoned and space was available and cheap, and people who were either not wealthy enough or the wrong color or otherwise couldn't participate in suburbanization were able to find places to live," Grant says. "People of color and immigrants... did their best to ride out the disinvestment."

The United States is an outlier in this respect, he says. In Europe, cities, with their dense agglomeration of services, transit options, and infrastructure, have historically been perceived by the wealthy as desirable, while many affluent Americans came around to this point of view only recently.

"Starting in the 1970s and picking up steam in the 1990s, people with resources and choices 'rediscovered' cities, and the downside of the suburbs became very apparent," Grant says. "Naturally, prices started to come up [in cities] and investments were made."

In this sense, gentrification is fueled by individuals—those with the financial resources to move back to the cities doing so en masse. These wealthier buyers and renters, seeking the same dense, walkable, transit-accessible neighborhoods that lower-income communities sought or were stuck in before them, began competing with these communities for limited housing, which resulted in displacement pressure.

"If the existing community owns housing stock, as is the case in many cities, they have the option of cashing out, for better or for worse, as land accrues value," Grant says. However, "It’s very different in renter neighborhoods. Renters are much more vulnerable and they have no way of benefiting from investments, unless they’re able to stick around because of rent regulation."

New York, as it happens, is a city of renters, with only 31 percent of residents owning their apartments.

The notion that development causes gentrification is a fallacy, Grant adds. In fact, it’s the other way around.

"Development goes in to meet demand because people want to live in a neighborhood," he says. "People tend to see rents going up and they see a new building and think, 'That building caused my rent to go up.' But both are in response to the demand of people to live in that neighborhood."

Clamping down on development in response, then, may only exacerbate the problem, by further limiting the supply of housing in a neighborhood that people find desirable. Grant points to the West Village, where restrictive zoning and landmark laws limit the ability to build, as an example of gentrification occurring independently of development.

"One reason we have such intense gentrification pressure in urban neighborhoods is that we stopped building them in 1929 after the stock market crash. We started building again after World War II—in suburbia," Grant says, speaking very broadly. "So now we have a scarcity of urbanism when the cultural preference is for urbanism. Who's going to lose the bidding war? Low-income people and people of color."

Potential solutions: Upzoning, penalizing absentee owners, and more

Articles explaining how to be a "good gentrifier" abound. Take this one from Bustle, which advises newcomers to gentrifying areas to talk to their neighbors and support long-running businesses.

This is well-intentioned, Weaver says, and it is a good idea for gentrifiers to be aware of their advantages and join the fight against policies that benefit them at the expense of their neighbors. But at the end of the day, she says, the actions of atomized individuals won’t suffice.

Gates of the Regional Plan Association sees the potential to mitigate displacement in government taking a different approach to development.

"The idea is that people are priced out of Brooklyn Heights, so they move to Park Slope. Then they’re priced out there, so they move to Bed-Stuy, and we have to build in Bed-Stuy to meet demand," he says. "Instead, we could up-zone Brooklyn Heights to meet demand. There are a lot of places that don’t enter the conversation" in terms of where to rezone and develop, he says.

Opening up low-rise, rich neighborhoods of homeowners to new development would be a heavy lift politically, as any number of NIMBY activist campaigns against tall buildings, in neighborhoods affluent and otherwise, have shown. There are also legitimate infrastructure capacity issues to consider, as anyone who has ridden the L train through Bloomberg-upzoned Williamsburg lately will tel you, not to mention anyone who is contemplating the effects of the impending L shutdown.

Another options that Gates proposes is optimizing existing property to boost the housing supply. He points to Bay Ridge as an example of a neighborhood with restrictive rules about keeping houses single-family, a policy that could be changed to allow for houses to be subdivided into multiple apartments. This has already been done in other brownstone neighborhoods. Another group has proposed legalizing basement apartments as a way of tapping into residential space in the city with out having to fire up a single backhoe.

Gates also sees potential in creating policies—a pied-a-terre tax is an oft-mentioned one — to curtail the use of second homes in the city.

"Manhattan has 44,000 second homes, a three percent vacancy rate, and the most expensive rents in the nation," he says. "There probably should be policies in place to deal with that."

Weaver, too, says that the housing supply has to be increased in order to offset gentrification and displacement.

"The city needs to use public land to build deeply affordable housing for people who are at most risk, as speculative capital flows into neighborhoods," she says. "The entire city is attractive to investors, and the role of city government should be to build at the bottom and implement strong anti-displacement measures. There’s no reason for them to do planned gentrification—the market is doing that on its own."

At the close of his book, Moss shares his wish list for addressing gentrification, including a moratorium on luxury construction, an expansion of residential rent regulation, and the creation of affordable housing independent of high-end development. He concludes that despite all the casualties, "The True New York is still there, hidden in the gaps... This is why I stay."

What can the average New Yorker do about all of this?

The City Council and the mayor make decisions on land use and zoning. New Yorkers concerned about these issues should learn where their representatives stand , and reach out to make their voices heard. Find out who your councilperson is here.

For information on contacting the Mayor's Office, click here. For a more detailed rundown of contacts at city agencies, as well as county, state, and even federal agencies, check out the New York City Green Book.

The bulk of rent regulation laws are the purview of state government, which means New Yorkers may want to familiarize themselves with the positions of their Assembly members and state senators. To find out who your senator is, click here. To find your Assembly member, click here.

President Trump is also seeking to cut as much as $6 billion nearly $9 billion from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, including funding for whole programs that New York and other cities rely on to finance the construction and operation of affordable housing. For information on how to contact the White House click here. Directories for the House and Senate are here and here.

On the most tangible level, New York tenants have more power in numbers when fighting to improve conditions and keep neighbors from getting evicted. Click here for our guide on how to start a tenant association.

You Might Also Like