Redevelopment plans for Crown Heights' Bedford-Union Armory prove divisive

The Bedford-Union Armory, a structure built in Crown Heights at the turn of the century to house members of the National Guard, has stood empty for years. But now, a redevelopment plan for the vast space is sowing divisions among residents and stakeholders in the Brooklyn community.

The city purchased the Armory in 2013, and then engaged Slate Property Group to convert the site into a multi-use complex; DNAInfo reports that last August, community groups, including the Crown Heights Tenant Union (CHTU) and New York Communities for Change (NYCC), rallied against the developer on the basis that the proposed revamp wouldn't deliver much-needed affordable housing to Crown Heights.

The plan comes at a time when Crown Heights is changing rapidly. In 2015, the New York Times spoke to a number of residents being displaced by rising rents; the article notes that the neighborhood's black population has dropped by 10 percent over the past decade. And last year, a documentary on gentrification in Crown Heights addressed the need to preserve affordable options for longtime locals.

Slate has since dropped out of the project, selling its shares to another developer, BFC Partners, but the opposition persists.

BFC's plan for Bedford Courts—its name for the project—includes a community facility; a 67,000-square foot recreational center that would offer space for sports, swimming, and other athletic events and classes; 330 new apartments, half of which would be slotted as affordable housing; and commercial space at a discount to nonprofits and small businesses.

The developer has already collaborated with the Local Development Corporation of Crown Heights and CAMBA to identify six nonprofit tenants, including the West Indian American Day Carnival Association and Ifetayo Cultural Arts Academy.

The argument over AMI and privatization

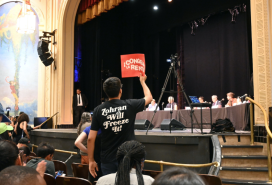

Many longtime locals, though, are dubious about the extent to which Bedford Courts would benefit the community. Gothamist reports that residents, housing advocates, and union workers rallied recently in favor of killing the deal, alleging that the affordable units that would be built would not be, in reality, affordable. The developer plans to make 18 apartments available to New Yorkers earning 40 percent AMI (area median income); 49 to people earning 50 percent AMI; and 99 to people earning 110 percent AMI.

As Brick previously covered, AMI is calculated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and is based on income data from throughout the five boroughs and surrounding suburbs. Currently, the AMI for a family of four in NYC is $90,600. Forty percent AMI is $36,240 and 50 is $45,300 (both considered low-income), while 110 percent AMI is $99,660, and is considered moderate income.

Gothamist notes that the median household income for residents of Crown Heights, though, is $41,870, meaning that only 18 of the apartments in Bedford Courts would be affordable to the typical local.

According to the official community health profile of Crown Heights, over a quarter of neighborhood residents are living below the federal poverty level; on average, tenants in Crown Heights are bearing a high rent burden, with 50 percent spending more than a third their income on housing. The report notes that unaffordable housing is "closely associated with poverty and poor health," and that low-income people have insufficient access to health care; the teen birth rate in Crown Heights is disproportionately high, as is elementary school absenteeism.

While the need for more affordable housing is urgent, Bedford Courts isn't the answer, argues a report from New York Communities for Change, a group that organizes in low- and middle-income neighborhoods to fight economic and racial injustice. In fact, writes NYCC, the development "will accelerate the whitening of Crown Heights, with fewer affordable apartments available for residents of color who earn lower incomes, and more apartments geared toward whiter, wealthier newcomers to the neighborhood."

The bulk of the proposed units at Bedford Courts—the apartments devoted to those earning 110 percent AMI, and market-rate apartments—will rent for above $2,200 per month. NYCC's report continues, "in Brooklyn, white families are much more likely to earn enough to afford one of the $2,200+ apartments than African-American or Latino families. About 58 percent of families who earn more than $75,000 are white, while only 26 percent are African-American and just 12 percent are Latino."

This will only hasten gentrification, the organization says, which is already well underway in Crown Heights: The Furman Center released a study last year revealing that the average rent in south Crown Heights has jumped by 18 percent over the past 20 years; many of the former residents the Times spoke to have been priced out, and moved further into Brooklyn or even out of the state entirely in search of greater affordability. And the city's Independent Budget Office identified Crown Heights as one of the neighborhoods from which the largest number of New Yorkers became homeless.

And the problems with the development go beyond affordability, says Joel Feingold, a co-founder of CHTU. "It's a transfer of wealth and power and public property from working class people to the rich," he says. "We see that in the affordable housing program, and we see it in the systemic orientation that this government has had for a long time to take public goods and give them to private developers to make huge profits from. This governing paradigm has to end: The government has to take side of tenants over landlords and workers over bosses."

How Bedford Courts could impact the community

Not all community members, though, see Bedford Courts as a threat to longtime residents of Crown Heights. Reverend Dr. Daryl G. Bloodsaw, pastor of the First Baptist Church of Crown Heights, wrote an op-ed for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in which he argues that the project will enrich the neighborhood. "Young people and seniors—and everyone in between—will benefit from free and low-cost programming in the armory’s new quality athletic facilities," he writes.

He adds that the affordable units are "a positive step," noting that middle-income earners need housing as well as low-income ones. "Here’s one thing I know for sure: If we kill the deal, we won’t get any more affordable housing. We will get nothing."

Geoffrey Davis, district leader for the 43rd assembly district and founder of the James E. Davis Stop Violence Foundation, says that bringing in a new education and recreation center would be transformative to the neighborhood. Many of the children he has worked with through his foundation have gone on to thrive as adults, he says, and attribute their success to having had a safe place to learn and socialize.

"This center is extremely important in the Crown Heights area," he says. "The bowling alley and the roller skating rink shut down. In this particular area, there's now no recreational or educational center for our young people to go to."

Feingold agrees that such a space is needed in the community, but says that it shouldn't be provided by a private developer. "Those are resources that we desperately need, but why has the city not provided this? Why do we have to make this Faustian bargain to get the resources working class people deserve?" he wonders. "We're questioning the entire model where the city gives money to the rich to provide public sevices. That should be decided by people who are directly affected."

While not all locals are persuaded that the project is ultimately a win for Crown Heights, fewer union members may be attending future rallies. The Daily News reports that BFC has come to an agreement with 32BJ SEIU (a union of property service workers) that the project, should it go through, will be staffed by union workers, and will offer a program to train locals to take on jobs as doormen, superintendents, porters, and other building workers.

Of the union agreement, Feingold says: "Our position is that it doesn't change the dynamics of the plan at all. It doesn't change the transfer of wealth in any appreciable way. It's a classic divide and conquer—we're aware of that and stand strong together."

With strong opposing sentiments about the project, the redevelopment of the Bedford-Union Armory could become a protracted one. There's precedent for lengthy battles: In the Bronx, efforts to redevelop the Kingsbridge Armory have been underway since 1994, delayed by disagreements between the city and community groups over the use of the facility and its construction. Today, the Real Deal writes, the plan is to turn the space into an ice skating rink, which Governor Andrew Cuomo plans to help fund, but Bronx borough president Ruben Diaz says that the city is continuing to stall the process.

Davis says that further conversations about the Bedford Armory are necessary. He cites his own conversations with BFC over the importance of providing affordable office space to nonprofits, which they since have done, including to his own foundation: "The West Indian Day Carnival will be there, too. There's an opportunity to educate young people to give them a sense of pride and dignity," he points out.

He acknowledges that affordable housing remains crucial for Crown Heights, but says that a move to kill the deal would be premature. "Of course, the housing component is important. People shouldn't be displaced," he says. "The opposition is saying just end it, and I'm saying negotiate. Don't just walk away from it. Work it out so people can have a place to stay."

You Might Also Like