In 'New York Rising,’ authors explore 400 years of the city's history

Governor Stuyvesant’s house, erected 1658.

Seymour B. Durst Old York Library Collection, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

Seymour Durst, son of the founder of one of New York City’s most prominent family-owned real estate firms, was a passionate collector of all things New York. Before he died in 1995, Durst amassed almost 35,000 pieces of New York history—books, prints, maps, photographs, and postcards. In the foreword to a handsome new book, "New York Rising: An Illustrated History from the Durst Collection," two of Durst’s children describe the size of their father’s collection housed in the family’s brownstone on East 48th Street: “When we began to fear for the building’s integrity, and thus his safety, he agreed to move the library to a brownstone on East 61st Street.” By the end of his life, the five-story house could barely accommodate the collection.

In 2011, the collection was moved from Durst’s home to Columbia University’s Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, where 20,000 of the items in the collection were subsequently digitized and made accessible.

In “New York Rising,” which is scheduled for publication on November 20, 10 scholars, all connected in some way to Columbia University, chose items from the Durst collection and occasionally images from other sources to tell the story of New York’s development over the past 400 years. The scholars, all well-known to anyone with an interest in NYC history, are Russell Shorto, the late Hilary Ballon, Andrew Dolkart, David King, Carol Willis, Hilary Sample, Reinhold Martin, Richard Plunz, Ann Buttenweiser and Lynne B. Sagalyn.

Each was asked to contribute an introductory text illustrated with annotated reproductions of items from the Durst collection. The 10 resulting chapters, compiled and edited by Kate Ascher and Thomas Mellins, trace the city’s history from “Laying the Groundwork 1640-1800” to “Remaking Times Square 1980-2000.” (The Dursts had a particular interest in Times Square; their company built 4 Times Square, the skyscraper that spurred the re-vitalization of the neighborhood).

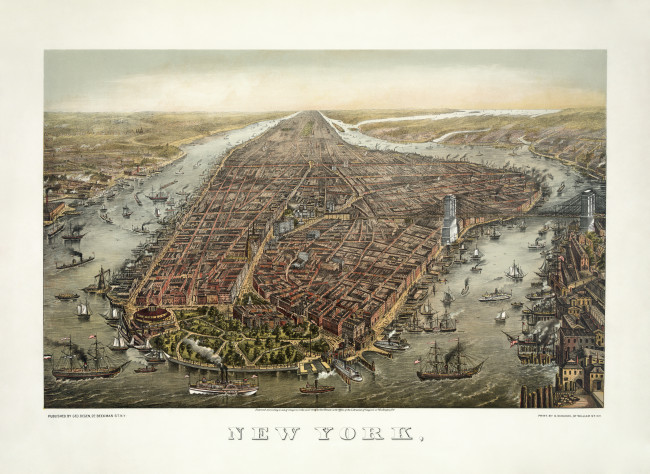

In an introduction to “New York Rising,” Mellins and Ascher write that the book examines aspects of “the city’s civic and cultural realms.” They posit that “... the forces that have shaped Manhattan’s urbanism are not primarily natural ones: the fires, floods and earthquakes that heavily influenced the appearance of cities such as Chicago and San Francisco have been largely absent from the history of New York. Instead, it has been people, politics and money that have been responsible for the transformation of a small trading post at the mouth of a protected bay into one of the world’s greatest and most vertical cities.”

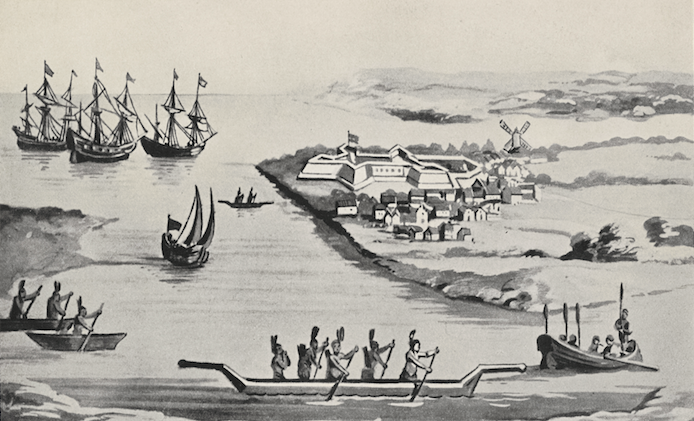

While the essays make interesting reading, what comes next is even better. The Portfolio section, where the items from the Durst collection are explained in the context of the chapter’s theme, is what makes the book unique. Along with the visual treat, the reader gets bits of history, even gossip from the past. For example, in a text accompanying a print of Governor Peter Stuyvesant’s house from 1658 (shown top), Shorto writes that most of the governors of the Dutch colony of New Netherland lived inside the fort but “when Peter Stuyvesant arrived in 1647… with a wife and budding family, he had no interest in having his domesticity impinged by living in close quarters with dozens of soldiers.”

“New York Rising” is a companionable guide to how the city got from there to here, from the image of a 1628 print of Fort Amsterdam, with its tiny houses clustered just outside the fort, to the final image in the book, a contemporary photo of Times Square.

One of the more striking ideas that emerges as one reads “New York Rising,” is the fact that some of the problems that the city faces today have either been with us for decades or can be traced back to an earlier attempt to solve an urban problem.

About a 1915 photo postcard of the then-new Equitable Building at 120 Broadway, Carol Willis notes that the building “cast many of its neighbors into perpetual shadow stealing their daylight and rents." Willis writes that objections to the new building resulted in the city’s first zoning law in 1916, instituting the “setback” principle, designed to guarantee a measure of light and air at street level. One hundred years later, people are still out demonstrating against the “super talls” and the shadows they cast over Central Park or low-rise neighborhoods.

In the chapter entitled “Moving the People 1880-1950,” David King points out that at the end of the 1800s, “transportation innovations were designed to accommodate vibrant street life” but that by the mid 1900s “streets were no place for enjoying the city. People were to be safely tucked away. Cars had conquered the street.” The result? Just ask anyone who bikes to work.

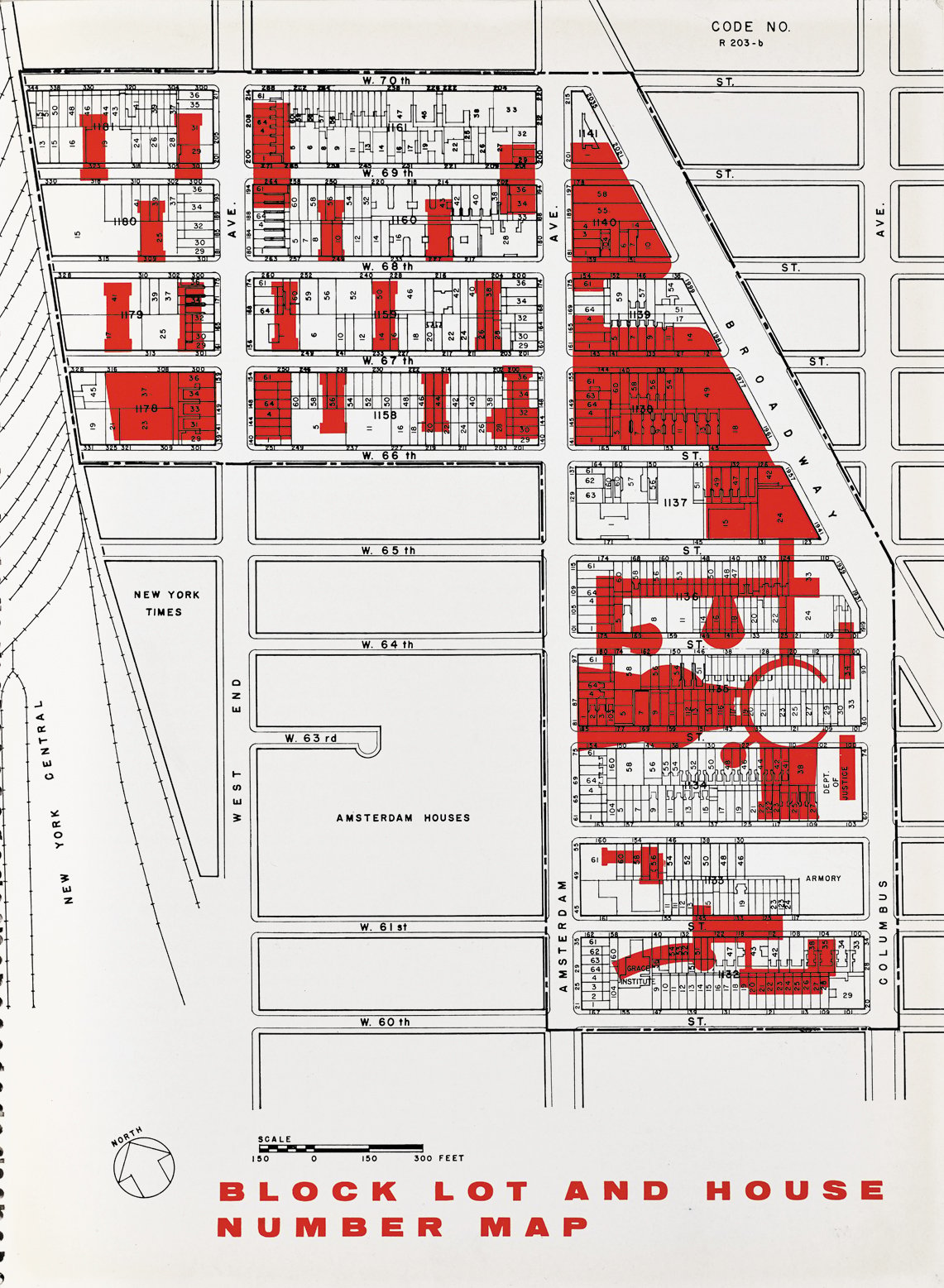

“New York Rising” also chronicles the dramatic change that the city experienced in the 30s, when enthusiasm for slum clearance was at its zenith with Robert Moses leading the charge as head of the NYC Slum Clearance Commission. (This was a euphemism-free age.) In commentary accompanying an image of a brochure about Harlem River Houses, a first-generation NYCHA building, Hilary Sample writes that in 1935, NYCHA boasted that it had demolished more than five miles of slums. In her chapter on “Housing the People 1930-1970,” Sample combines words and images to illustrate how so many low-rise Manhattan neighborhoods were bulldozed, their residents forced to relocate and, in many cases, to abandon Manhattan for good.

The era of slum clearance entirely changed the face of Manhattan. Consider the area around Lincoln Center, once a neighborhood called San Juan Hill, which had been home to the largest population of African Americans in the city. Today, no trace of that neighborhood remains, replaced by the performing arts center and Amsterdam Houses, NYCHA housing built to replace the original tenements. Ironically, the first residents of the NYCHA development were primarily white.

NYCHA, described by Mellins as “NYC’s ambitious plan to provide affordable housing for New Yorkers after the Great Depression,” is an excellent example of how a one-time solution has become a problem.

“In 1934, the establishment of the New York City Housing Authority, which built, owned, and operated housing for the working class and poor, was a watershed; it was the first such authority in the country and it immediately embarked on a remarkable building program, dwarfing that of any other American city. Today, a minimum of 400,000 people live in NYCHA developments, with some estimates as high as 600,000. Despite the formidable challenges facing NYCHA now, around 200,000 people are on waiting lists for public housing, and unlike many other cities, including Chicago, New York has demolished virtually none of its public housing stock. We are, in some ways, currently witnessing the difficulties of maintaining such a vast portfolio, the direct result of the city's vast ambitions.”

“New York Rising” is the perfect book for readers who want their NYC history in short, clearly written and abundantly-illustrated doses. The quality of the reproductions in the book is particularly impressive; its design and layout, credited to Yve Ludwig, deserves special mention. The Durst collection is a wonder and the contributors and editors have certainly done justice to its remarkable scope in this new book.

Two complaints, however: first, there seem to be more typos than there should be in a book produced in cooperation with a major university. The very last line of text in the chapter on “Remaking Times Square 1980-2000” reads: “It is the quintessential urban place, not really predicable (sic), however cleaned up it looks, however benign its latest activities.”

Second, and more importantly, there is no index. In a book covering such a broad span of history, it would be helpful to be able to seek out specific topics, to be able to look up “Commissioners’ Plan of 1811” or “the Singer Building,” without having to thumb through 261 pages to find it.

Complaints aside, this is a beautiful book and a useful addition to your New York history bookshelf. Its size makes it a coffee table book but don’t let it sit on the coffee table. Move it to your bedside table, or wherever you put the books that you are really planning to read.

"New York Rising: An Illustrated History from the Durst Collection" by Kate Ascher and Thomas Mellins, published by The Monacelli Press in association with The Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation and Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, 2018

You Might Also Like