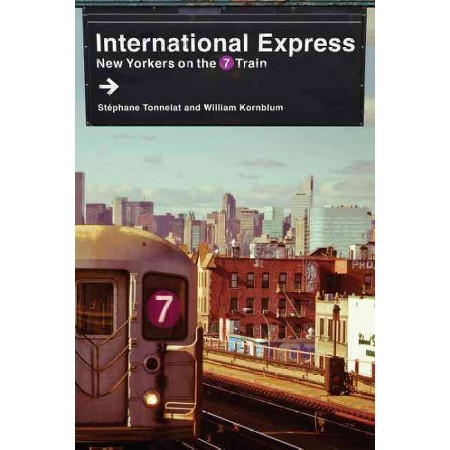

The authors of a new 7-train book on immigrant communities, MTA woes, and being a "competent" passenger

"We become New Yorkers on the subway," begins International Express: New Yorkers on the 7 Train, by Stéphane Tonnelat, an urban sociologist and researcher at the University Paris Nanterre, and William Kornblum, also an urban sociologist and emeritus professor at the CUNY Graduate Center. The book explores the rite of passage that is developing the know-how, patience, and resilience to use the New York City transit system, with an eye on how that unfolds along the 7 train, the line dubbed the "International Express" for its pathway through many of Queens' immigrant communities.

The 7 train corridor is a very different place from the one Kornblum, a native New Yorker, knew as a child of the 1950s: Immigrants from across Latin America and Asia have since transformed neighborhoods along the route into ethnic enclaves. And each day, newcomers to NYC must learn to navigate the multifarious, and often malfunctioning, world of the subway. Tonnelat and Kornblum identify "competencies" that one must learn to travel in relative comfort, the moral dilemmas passengers face in daily scenarios like a woman being harassed by a fellow rider, and the frustrations born from the aging system's delays and overcrowding.

We spoke to the authors to find out more about what they discovered in their investigation of NYC's most diverse train line.

What kind of changes have you noted along the 7 train corridor in recent years? What kind of role might gentrification be playing? Are there any concerns that Queens' internationalism could be at risk, as more affluent New Yorkers start moving to Queens from Brooklyn or Manhattan in search of greater affordability?

As regular riders of the 7 train, we have not noticed all that much evidence of gentrification that would significantly change the diversity of populations along the trains' route through much of northern Queens. Development in Long Island City is bringing a more upscale ridership as the train reaches the East River. In Jackson Heights, there is upward movement of property values, and apartments in the historic buildings are attracting Manhattanites and others seeking more affordable larger apartments. But this is not, technically speaking, gentrification.

Why wouldn't that be considered gentrification?

There has been a middle class population in Jackson Heights for generations, so young families from professional backgrounds who are moving into apartments sold by elderly residents or their estates are not necessarily displacing less affluent tenants living outside the historic buildings, especially those with center gardens. It's essentially replacement rather than gentrification. In the longer term, however, as prices and rents rise, we can expect some replacement gentrification as well.

The subway can be an "equalizer" in the sense that New Yorkers of different ethnicities, nationalities, and incomes find themselves crowded together in one small space. What are some of the advantages and disadvantages the passengers you interviewed identify about this?

No one we spoke to said they enjoyed subway crowding, and from time to time, some complained about being forced to squeeze in next to people whom they sensed were "foreign." But overall, 7 riders tended to "get along to go along," which in practical terms means they are less concerned about ethnicity and race than about individual courtesy and subway competence. Some even said they learned a lot about other groups and nationalities over their years of riding the trains.

Overall, the subway is a great equalizer in the sense that it offers New Yorkers access to the whole city independently of race, ethnicity, gender, or age (within limits). It does not mean that there is no discrimination or harassment on the train, a problem that we discuss at length, but that thanks to the subway, equality of access becomes a generally shared value. This is one of the characteristics of the subway that help riders become New Yorkers.

Your book explores the competencies that come with being a regular subway passenger. What are some of the best practices for riding the subway that you discovered?

Besides knowing how and where to go and avoiding trouble, subway competency can mean the rider knows how to makes moves that enhance their own comfort. And it can mean that competent riders know how to do things that enhance the experience of others in different situations. A rider may be extremely good at getting a seat or knowing where to stand so as to be likely to get a seat soon. Other riders may break out of the anonymity of the rider's role and speak out to warn others away from danger or trouble. These are the most competent riders from the perspective of the entire subway community.

New Yorkers are often united by their frustrations with the subway. How did you find that the problems with our transit system—crowding, delays, service changes—impacted the communities along the 7 line?

Service disruptions such as delays and service change are a serious problem for communities along the 7 train. Except for a few stops on the LIRR at Flushing and 61st Street, there are no efficient substitute options for riders who need to get to Manhattan. Shuttle bus services are very slow and cannot cross the river. Many inhabitants in the service industry work on weekends when construction often halts service.

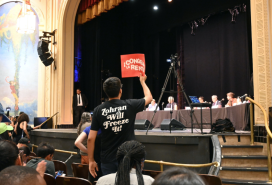

Despite growing frustrations, riders have not yet come together to demand better service. In this regard, it is difficult to say that New Yorkers are effectively united. Recently, thanks to the power of social media, new organizations such as the Riders Alliance have been reaching out to more riders and it seems that they are gaining the attention of the MTA and the governor, [who is] effectively in charge of the MTA. We conclude the book by saying that the public sphere emerging out of social media may be a new chance for the subway to be recognized as a true public service worthy of public investment.

With the Trump administration's immigration policies, residents of many of the communities along the 7 line are contending with increased anxieties over the possibility of harassment or deportation at the hands of ICE. How do you see this impacting daily life on the 7 train?

The status of immigrants is not visible in the subway and indeed, a lot of riders on the 7 train do not have US citizenship or even official resident status. In our interviews we did not ask riders about their status, but the more indirect evidence of an insecure populaton due to immigration status abounds along the #7 train: The existence of casual outdoor labor markets (men seeking day work -- not something workers with legal status usually resort to), the number of organizations devoted to the needs of the legally precarious, the ads for legal services, etc. Now one hears increasing stories of children in schools whose parents are facing deportation. See also the excellent film In Jackson Heights, by Frederick Wiseman.

The risk of deportation is present when police officers stop riders who they believe are evading the fare. Jumping the turnstile can be classified as a class A misdemeanor by the officers, which automatically sends the rider to court. Most of the accusations are dismissed by the judge, but for riders who have had previous brushes with the law, who have an outstanding low level warrant or are undocumented, this can mean jail time or deportation.

Some studies have shown that young males of color are more at risk of being charged with misdemeanors than other riders who more often get a ticket. As a result, these riders and undocumented immigrants have a serious incentive to pay the fare and behave on the subway. A recent progress for inhabitants of neighborhoods along the 7 train is the New York City ID card. The card is accessible to all inhabitants with proof of address and legally valid in case of police stops. It may help communities along the 7 train to cope with the anxieties over harassment and deportation, although we do not know of any study about the effect of this card yet.

You Might Also Like