Talking gentrification, and why "New York City is a real estate story," with the director of HBO's "Class Divide"

Daphne Pinkerson

The story of gentrification has been told many times over as development rapidly transforms New York City. But the new HBO documentary, Class Divide, takes an in-depth and personal, and some would say more heartbreaking, look into the cost it exacts on the children that inhabit one city block: West 26th Street in west Chelsea.

The film focuses on the stunning juxtaposition of the lives of children living in the Elliott-Chelsea housing project on the east side of Ninth Avenue and the lives of their affluent counterparts who attend the tony Avenues school on the other side of the street. The literal railroad on which the multi-milllion-dollar High Line now sits highlights the proverbial "right" and "wrong" sides of the tracks, a symbolic line that bifurcates two worlds. Yet we see children from both sides enjoying the High Line and playing in the same parks, some living four to a bedroom and others living in $10 million townhomes, just steps from one another.

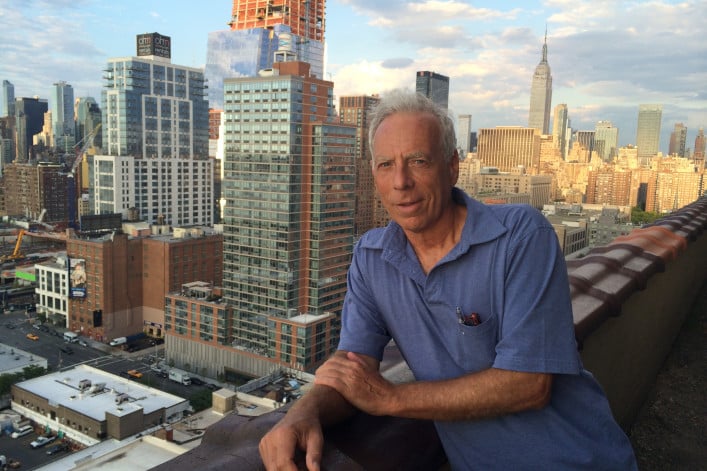

Brick Underground recently chatted with the documentary's director, Marc Levin, who let us in on his motivations for making the film, his personal take on changes in the area where he has resided for the last 40 years, and the good, bad, and the ugly of the oft-dreaded g-word.

Why did you focus on this block in particular?

Because I have lived on this particular block on 26th Street for over 40 years and have worked nearby at 601 West 26th Street for 17, so I have personally witnessed its many changes. I joked at some of the screenings that when my future mother-in-law saw where her daughter ended up—in a factory on 26th Street—she started crying. She must have imagined a more glorious future for her—a suburban home. But had she lived and visited now, she'd be stunned at how the area has changed. A Hilton Hotel is now on the street; Avenues is across the avenue.

How did you originally find your apartment all those years ago, and what drew you to the area originally?

I had been living in the West Village with roommates. But then I moved into Chelsea with a bunch of guys back in the ‘70s. My sister and a buddy found our 4,500-square-foot industrial loft space which rented for about $400/month at the time. There was no heat on weekends and there was a garment factory above and below. But we didn’t care. It was a party loft and we moved there because it was near Madison Square Garden. We were all Knicks fans and we’d just walk and buy tickets from scalpers when we could.

How did you end up living there sans roommates and eventually with your family?

Eventually an artist in my building, who was also a contractor, realized how the area was changing. A group of us got together to buy the building when it turned co-op.

Ah, so you are an OG!

Yes, you can say that!

When you are young and living in non-residential area, you don’t care. NYC was on its ass but we just didn’t care. But as I grew up, I raised my kids there so the way I looked at things changed. In some instances I wondered if I had made a good decision. Once we walked by a parking attendant that was just shot dead in a crack deal gone bad. We saw part of that and it was frightening. Then somewhere in the ‘90s as the boom started, we saw the area change. I’d walk Sixth Avenue to the Village and back. Condos and high-rises were going up on 23rd and 34th.

Then I got my studio in the ‘90s and the High Line was just a place you had to dodge the pigeon shit. Who would have thought it would become what it is now?! And 26th Street was all talk show studios. It is now the art capital of the world.

So I was seeing all these things on my daily walk to work and taking my kids out. So I began thinking, “How can I tell this story?”

Moving into my space in that rental in many ways created a lifestyle for me as an independent artist.

So real estate is at the center of this whole tale?

This is a real estate story, no doubt about it! But then again, New York City is a real estate story. I ended in the epicenter of a neighborhood that changed so dramatically and this film became an opportunity to put all that on the screen.

What was it like for your own kids to go to school back in the day?

This was a big discussion. They went to preschool at Hudson Guild. There’s a public school on our corner of Ninth Avenue—PS 33—and I had gone to public school so I said let’s do that. My wife vetoed that idea because she explained that school was a total failure (in the late ‘80s.)

Interestingly, that school now has an advanced placement track and is attracting kids from all over city. If it were today I might send them there. Instead they went to Little Red School House in the Village.

Witnessing the lives of select children living in the Elliott-Chelsea housing projects versus the pressures of the kids who attend Avenues, what are the biggest differences and commonalities?

The biggest takeaway is that there is common ground of shared anxiety about where young people fit in rapidly changing future on both sides of the street. Kids in the projects have economic struggle that the others don’t. There’s this added stressor for them—a changing political environment for which the very concept of public housing seems alien. There is no guarantee they will have a social safety net. Will their homes still be there and what will happen to their extended family?

On the Avenues side of the street—you would think kids of more privilege wouldn't share in future anxiety. But they realize they aren't just competing with students in the U.S.—they are competing with students globally: Chinese, Russians, Indian. While their parents are successful, will they do as well now that this is a more global game? They are aware their parents are paying for them to go to school and get into a good college. One student interviewed in the documentary says that he has wanted to go to Harvard since he was four years old. They go to a school and live in a place where they see changes right in front of their face. The landscape changes day-by-day in West Chelsea.

[Warning: The section following includes a pivotal spoiler from the movie.]

When you set out to film obviously you would have no idea that the Avenues student Luc Hawkins would commit suicide. The movie offers no information or commentary about this shocking occurrence, but do you feel it is telling that he succumbed to that pressure even after explaining how many advantages he realizes he has?

Luc's suicide was shocking—total stunner. We weren't aware, nor were his friends, of any health issues or depression. It is simply tragic. We have spoken to his family and they also feel it is a mystery. His family saw the documentary at the premiere and thanked us for immortalizing their son.

How did you find candidates to speak to from Avenues? I read an interview in which you said that it was easier to get those in the projects to speak than getting the more affluent students from Avenues to participate.

It's harder to get into an elite private school than it is to get into the CIA or to film or Death Row in Texas where I’ve filmed. There was tremendous apprehension amongst families of Avenues’ students. The exorbitantly rich want privacy and have their own fears about publicity.

My relationship with Hudson Guild was helpful in finding those living in the projects to participate. I used to play basketball at the courts the guys play at. Also, work we've done in the past deals with urban issues so there is a familiarity with our work from people living in the projects. They know my work better than those in Avenues.

Gentrification in NYC is nothing new—what struck you as being significant about this particularly enclave?

Gentrification is part of the story of New York City. My producer, Daphne Pinkerson, is in the area as well in London Terrace. We were able to approach everyone in the film from Community Board 4, to both schools and the projects. We've seen it from all angles because we are not outsiders. We live here; we work here. There are no bad or good guys. It's complicated.

So there are good changes: The PS 33 is a success story and so is public safety. It used to be the Wild West side. There is an upgrade in amenities. The High Line and the park on 29th are specular ones and all within the last 15 years.

And obviously there are real problems with gentrification as well: Small shops and friends have been displaced, the influx of new stores and eateries are expensive. For people who live in projects, many have to shop in New Jersey or the Bronx because there are no affordable food stores.

Let’s not forget one of the biggest problems: housing costs and rents. I am at the end of a long-term lease and I will not be able to keep my studio in this area if rents go up exponentially as they have been.

I've been the pioneer — and now I’m being pushed out.

It seems to have come full circle, sort of like the food chain.

Exactly like the food chain! And I wanted to make a movie that integrates this cycle.

You Might Also Like