How to check a neighborhood’s climate disaster risk before you move

- Search rainfall maps and the city's adaptation measures for extreme weather

- You can also find a neighborhood’s level of air pollutants online and check its flood zone

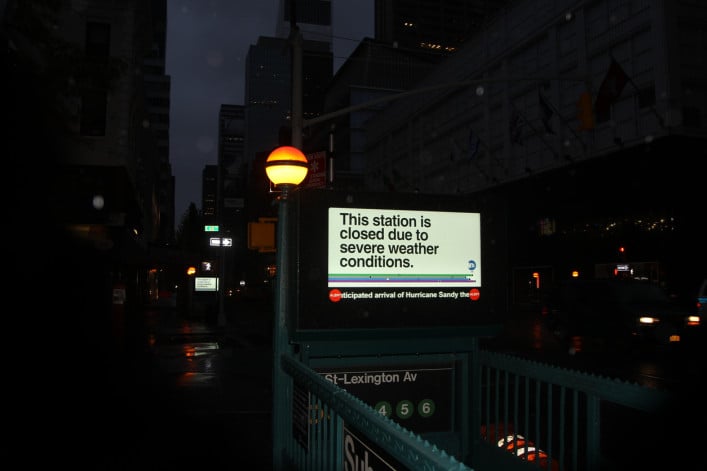

A 2012 digital display above the entrance of a subway station warns passengers about incoming Hurricane Sandy.

iStock

When Hurricane Sandy hit Red Hook, Brooklyn, nearly every block was inundated in the flood. It left the neighborhood’s public housing without power or clean water for weeks. And came right up to Maryana Grinshpun’s doorstep.

“The water came up to the top of the stoop—the entrance to our apartment—[but] we didn’t get flooded,” says Grinshpun, a founding partner of architecture and design firm Mammoth Projects. “All of our mechanical systems, like our heating, were in the basement, so all of that was shot. We had no electricity or heat or hot water for about a month, which was really difficult.”

Because of the damage, Grinshpun moved out about six months later as Red Hook’s recovery took shape. But in the years after Sandy, the waterfront neighborhood grew. Developers built 27 new residential buildings in the five years after the hurricane, and the median sales price jumped from $580,402 in 2012 to $1.35 million in 2023, according to StreetEasy. Politico even called the neighborhood an example of “climate gentrification” as a more affluent population moved to the waterfront properties.

But that growth hasn’t convinced Grinshpun to return to Red Hook. As she prepares to buy a home in the next two years, she’s looking at neighborhoods with higher elevations that are more protected from flooding expected to grow worse with climate change. She’s not going to buy in Red Hook and she’s certainly not buying a summer home in the Rockaways.

Global climate change is expected to make storms like Sandy worse in the coming years, and flooding isn’t the only factor New Yorkers should weigh when deciding when to move. Air quality—given smog that blanketed NYC during the Canadian wildfires—and NYC’s climate adaptation measures are two crucial considerations when evaluating a neighborhood’s resilience to climate change.

Luckily, there’s a handful of ways would-be homebuyers and renters can consider climate change when relocating, including an area’s flood risk, air quality, and local climate adaptation measures. Read on for a list of factors to look into when evaluating a neighborhood’s climate change risk.

[Editor’s note: This story is part of a new, ongoing series about how you can take into account climate change when purchasing a home. You can read our first story, about an individual building’s climate change risk, here. This article was originally published in September 2023. We are presenting it again as part of our winter Best of Brick week.]

Know your flood zone

Rising sea levels and more frequent storms are likely to worsen flooding in neighborhoods home to NYC’s public housing and upscale waterfront properties. Hurricane Sandy alone damaged 35 NYC Housing Authority developments in 2012, and by 2080, similar storms could flood more than 50 NYCHA complexes, Gothamist reported.

But pricier areas like Greenpoint and Williamsburg in Brooklyn, Long Island City in Queens, and Hudson Yards in Manhattan are also at risk because of their proximity to the waterfront. Climate change has made Ellen Sykes, a real estate broker at Coldwell Banker Warburg, more cautious about coastal neighborhoods.

“Who wouldn’t want to live on the water? It’s tremendous to be able to do that, but I think long term—and here I’m talking about young people—you’re going to spend a lot of money on an apartment so think twice about it because maybe you're going to be in it for a long time,” Sykes says.

Doug Bowen, an agent at Douglas Elliman, also advises caution—to an extent. Bowen owns a rental property in Red Hook that was flooded during Sandy, and says that just as he was able to rebuild his building, NYC has shown that it’s been able to come back from multiple disasters.

“I think you have to be aware of the potential for catastrophe in anything that you buy,” Bowen says. “New York is incredibly resilient. It showed its ability to bounce back many times and I consider it to be the greatest place to live in the world.”

If you’re considering moving to a new neighborhood, you should check the area’s flood zone. You can also search the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s flood maps, find out if your neighborhood has an underground river, and search NYC’s rainfall-based flood maps online. (Just remember that if a neighborhood isn’t in a flood zone, it can still flood thanks to heavy rainfall or a backed-up sewer.)

Every breath you take

Despite its reputation as a smoggy metropolis, NYC’s air quality has significantly improved since the city began monitoring it in 2009, according to the NYC Community Air Survey.

Fine particulate matter—small particles that can penetrate the lungs and bloodstream, worsening lung and heart disease—dropped by 40 percent from 2009 to 2021. During that same period, levels of sulfur dioxide—which can worsen lung diseases and asthma—declined by 97 percent thanks to a push for cleaner heating oils.

If you want to live in an area with slightly less smog, you can check a neighborhood’s air quality via the NYC Community Air Survey’s online map.

Air quality is important because you do want to be able to get fresh air into your apartment from the outside when it's safe to do so, says Andrew Wilson, regional director for engineering and architectural design firm O&S Associates. Luckily, NYC’s air is, for the most part, easy breezy.

“NYC’s air quality is actually very good in comparison to most of the major metropolitan areas in the country,” Wilson says. “As an engineer, the way that I would look at it, I would be concerned with getting fresh air in from the outside and with the efficiency of my systems rather than the anomalous one time event that we had in 2023.”

Building better neighborhoods

In Sandy’s aftermath, FEMA spent a solid chunk of change to rebuild the regions damaged in the storm. To date, FEMA alone has spent $14.1 billion to rebuild public infrastructure and awarded more than $1 billion in grants to individual households in New York state. But the city has gotten a slow start on many infrastructure projects meant to protect the coastline and its inhabitants.

The city began construction on part of four initiatives meant to protect Lower Manhattan from sea level rise and storms just last year. Another plan, to deploy 2.4 miles of floodwalls and flood gates on Manhattan’s East Side, broke ground in 2021 after six years of planning. And as of last year, the city had spent just 13.3 percent of the $1.9 billion allocated to that effort, dubbed the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project, according to a report from the NYC Comptroller.

While slow-going, these projects are essential to protect coastal and low-lying neighborhoods from the consequences of climate change. The city currently has plans covering Lower Manhattan—including the Seaport, Financial District, and Battery Park communities—Red Hook in Brooklyn, the Rockaways in Queens, and the south shore of Staten Island, according to the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice. You can read up on your prospective neighborhood’s coastal resiliency project here.

There’s also a handful of smaller projects helping neighborhoods weather worsening…well, weather.

The NYC Department of Parks & Recreation planted 13,000 trees in the 2022 fiscal year to help combat extreme heat, according to the city. In January, Mayor Eric Adams expanded a city program that helps manage rain-related flooding to Corona and Kissena Park in Queens, Parkchester in the Bronx, and East New York in Brooklyn. The city is also working to upgrade its outdated sewer system, particularly in southeast Queens.

Planting trees and other types of green infrastructure—such as green roofs—can seem like insignificant steps. But little projects go a long way to mitigate climate change-related problems like flooding, says Mona Hemmati, a postdoctoral research scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University.

And residents need to be aware of these infrastructure measures when looking for a home.

“Scientists, government, and local planners need to make sure to provide this information as much as they can to residents so that they can make an informed decision about their locational choices,” Hemmati says. “The local government also has a responsibility to provide a strategy to mitigate the risk through applying different types of structural and non-structural mitigation measures.”

Would-be homebuyers can find more information on neighborhood adaptation programs on the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice’s website.

You Might Also Like