Top 10 reasons NYC's small landlords are becoming extinct

A hundred years ago, men and horses farmed vegetables, and most rentals were in owner-occupied buildings.

Today in NYC, we call those farmers "urban gardeners" or "Amish"--and artisanal, old-style landlords are just as uncommon. Here are the top 10 reasons why:

1. Rent regulation: Rent regulation, imposed in 1947 and again in 1971, did not provide enough revenue for small landlords to function. Small landlords burned their buildings, defaulted on property taxes (NYC owned two-thirds of Harlem and the South Bronx in the early 1980s), sold their buildings to the tenants (a.k.a. the co-op conversion craze of the '60s-'80s), or sold out to better financed (and bigger) landlords.

2. (Lack of) handiness: Being a small landlord requires being hands-on and understanding the intimate details of your building. Like most small landlords, I learned from watching my father and dealing with minor tenant issues. When my tenants have clogged sinks, I can fix them because I’ve seen it done before and I’m a fairly handy guy. If I had to keep a handyman on staff it would eat up most of my total rents. Many of the people who stay put in NYC grew up in apartments. So there aren’t a lot of people left who are qualified to be small landlords.

3. Money: Big landlords borrow more money at cheaper rates than small landlords can. Small landlords have to go to banks, and can only get a 10-year-loan for 60% or less of the value of a building, depending on actual rents. Tishman Speyer managed to borrow 80% of the money for Stuyvesant Town (mostly from pension funds), but their rents only covered 58% of the mortgage. Borrowing more allows bigger landlords to use a limited amount of capital to buy more properties.

4. Dealing with the Division of Housing and Community Renewal: Rent regulations are an incredible burden. To own a rent stabilized apartment, one has to use a complicated online system to register the rents, renew the leases at exactly the right time, save every receipt for years, making sure that the apartment number of any renovation is on it, and promptly file for rent increases for renovation projects.

Unfortunately, it can take 5-plus years to get a $20/month rent increase out of DHCR, and if you only have a few apartments, the cost of filing isn’t worth your time--it costs just as much to file for a rent increase in a small building as a large one, but the rent increase is proportional to the number of apartments.

Worse yet, DHCR’s group that deals with rent increases operates at geological time scales, while the “Tenant Protection Unit” (aka the Landlord Harassment Unit) can audit your expenses for everything you’ve ever done-- if you are missing even one receipt, your rents can get cut. Lots of small landlords don’t have the time or energy to deal with this stuff.

5. Dealing with the rest of NYC’s Bureaucracy: NYC has all sorts of uniquely expensive requirements (e.g. you need a special license to verify that your sprinkler isn’t falling off the wall each month, or it costs you $800/year to get someone to do it).

Even minor alterations require incredibly expensive permits and approvals and multiple inspections (with inspectors who don’t show up). Failure to play by the rules perfectly can expose you to bankrupting fines (e.g. my last landlord got fined $20,000 and got a stop work order because the inspector thought his scaffold was over 30’ high when it was only 29’ 7”).

God help you if you live in a historic district; every time you want to paint your house you have to hire an architect and a historian first. Most small owners don’t have the time to take off from work to deal with this stuff, and their buildings gradually revert to ‘estate condition’. When they sell, the buildings go to developers or large real estate companies.

6. Housing Court: A bad tenant can bankrupt a small owner. Small owners are often undercapitalized. If they only have three tenants, and one stops paying, thanks to NYC’s very tenant-friendly courts, he can stay there for nine months, at which point the owners will be facing foreclosure. Bigger landlords have more money and more paying tenants, so unless there’s a building-wide rent strike, they can survive some delinquent tenants. Some cases can go on for 10 years, during which time the landlord and tenant often share the same roof. Awkward!

7. Being an artisanal landlord requires skills in law, project management, tax policy, construction, architecture, and investment theory: The hours are terrible, and the work can be physically demanding and really smelly. The return on investment is also pretty poor. Anyone smart enough to do this job could make far more money doing other things, which is why the kids of small landlords often sell out rather than take on the responsibilities.

8. Condos: Individual homeowners can borrow up to 95% of the purchase price and they get a huge tax deduction that rental owners don’t get, so small buildings are often worth more as condos than as rentals. Lots of 4-12 unit apartment buildings have been bought by developers and condo-ized, further reducing the stock of small homeowners.

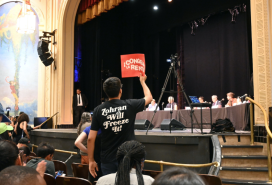

9. Politics: Each year I fork over $200 or so to the lobbyists to feed a few chicken legs to the State Legislature, in the hopes that they won’t mess up the real estate market even more. The big landlords can actually spend enough to buy new representatives; they view the $100-200 tribute per apartment per year as a cost of doing business. Suffice it to say that the rules are often written to favor the big owners over the small ones.

10. Mansionization: My former landlord converted his house from an 8-unit to a 5-unit building to get out of rent regulation. When he sells it, some hedge funder will turn it into a 2-unit mansion with a ‘"nanny apartment." Goodbye, small landlord!

A landlord speaks -- about what's behind that incomprehensible lease

Single and slightly antisocial? Have I got the place for you!

Rent Coach: My landlord says he's not allowed to take a bigger security deposit. Is that true?

BrickUnderground's 7-step guide for first-time landlords

Moving to NYC? Here's a crash course in finding an apartment here

Inside tips for amateur landlords

Tips for getting an apartment ready to rent

Advice for a pet-friendly landlord

When your potential tenant bugs you

Rent Coach: Can I advertise my apartment for rent to non-smokers only?

Rent Coach: What if my tenant won't vacate by the move-out date?