How your brain gets in the way of making smart real estate decisions

Photo: iStock/psyolacan

The rent's hiking up far too high, there's no escaping it, and you've resolved to move. But every apartment you check out doesn't seem to satisfy. This one's too dark, that one's too close to your ex, and what's the deal with the bright pink walls in that other one? Never mind that the dark apartment is actually quite spacious (and, it has to be said, can easily be brightened up with lamps), or that you're not even sure if your ex does still live around the corner. And the bubblegum walls? Gone in two coatings of Benjamin Moore. But instead of considering any of that, you re-up for your current apartment at hundreds of dollars more, and end up frustrated as ever.

What's going on? Call it self-sabotage or apathy or feeling overwhelmed, but whatever it is, it's likely that your mind is playing tricks on you, in a manner of speaking, says neuroscientist and The Guardian science columnist Dean Burnett, author of the new book, The Idiot Brain: A Neuroscientist Explains What Your Head is Really Up To. "People do have an inflated opinion about their rationality [but] it's not always justified," he says. "[They] tend to overestimate their abilities [in terms of making rational decisions]. They're sort of prone to more knee-jerk emotional reactions to things."

Familiarity is a big pull, he adds. "If you're in an apartment or a house that looks like a previous one [you've lived in], or like one you saw previously and wanted, that's going to be more appealing because it's not challenging or unusual," says Burnett. "Anything that's familiar or safe is essentially more prized than something unusual or weird."

Consequently, you may not move even if you really need to, or you might make the search much more difficult than it needs to be. "If you've lived in one place for, say, 10 years, and you want to get out for whatever reason—it's not big enough, it doesn't have the right layout, it's restricting your general lifestyle—and that's what you really ought to do, but it's very familiar to you, you're more likely to favor something that's like this place, even if it's not what you want. The brain adapts, the brain habituates to anything you're exposed to for a long period."

Compounding the situation, of course, is the magnitude of the decision. Choosing to buy or rent a new space is a bigger—and more expensive–proposition than changing up your exercise regimen or breakfast options. "Buying property is a massive investment," he says. "The bigger the investment, the bigger the risk, the more the brain sticks to familiarity and safety. It can be hard for people to take the plunge and buy something they're not used to."

For starters, the human brain is hugely averse to uncertainty and risk, he points out. "The brain likes to account for things and keep it safe," he says. "Uncertainty can mean potential danger, so there's an underlying dislike of it. So people need reassurances that they are making the right choice."

Here's how it plays out, real estate-wise. Any information that "conforms to what [a person] thinks will stand out," Burnett explains. So if you go to a neighborhood that immediately appeals to you, "anything that backs that up will be accepted more readily, and if they go to a less desirable area but will have a better property, the inherent bias that we have there will play a part in the decision that's made."

You may also be so paralyzed you end up doing nothing, even if it means staying in an apartment you can't quite afford. "You may be in apartment you can't afford, but that's more an abstract concern, whereas you can think to yourself, 'I'll make some more money soon,' or 'I'll spend less on this thing' and cut costs somehow," says Burnett. "You have to convince yourself that [a move] is worth the upheaval."

So how does the brain get in your way? Here, a few typical mental blocks:

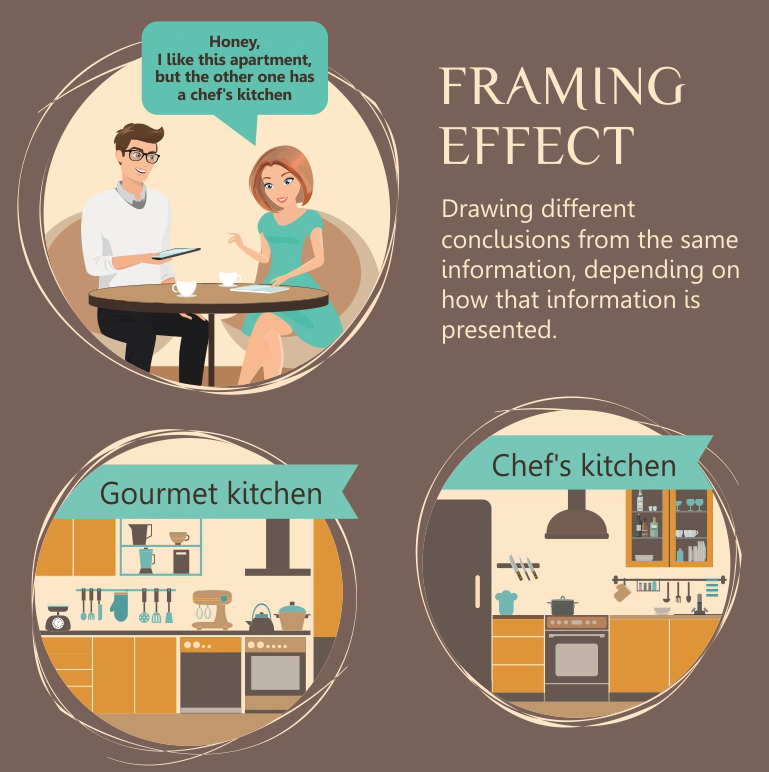

The framing effect

One cognitive bias that affects the way you make real estate decisions is the framing effect, defined by RentCafe, a rental database website, in a recent story about renter psychology, as "drawing different conclusions from the same information, depending on how that information is presented." A renter who loves to cook, for instance, may form a preference for a listing if the kitchen is described as a pleasant place to drum up meals—a "chef's kitchen," perhaps—rather than a utilitarian spot. "People think they know what a chef is," explains Burnett. "It smacks of professionalism and efficiency. These are things that [people] think they understand, or do understand but not in the right way."

"It's the way you phrase something, but you have to take into account the relationship between the potential buyer and the realtor," says Burnett. "If a realtor is a good one and is recognized as an authority on the property, then things they say will have more impact. If [the buyer] recognizes the person as an expert who knows what they're talking about, then the things they say will have more impact."

Illustration courtesy of RentCafe.

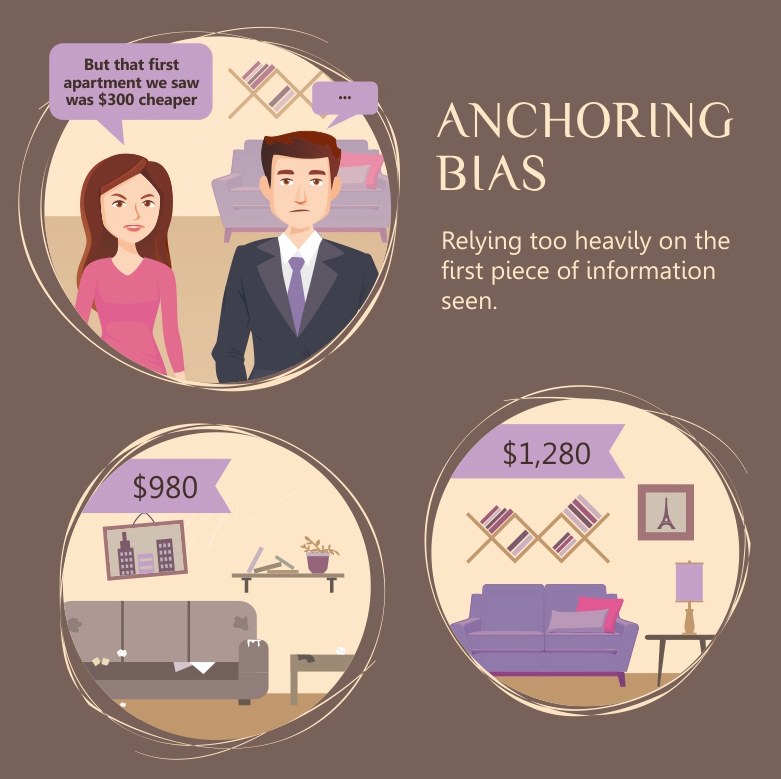

Anchoring bias

Science Daily explains this bias as "the common human tendency to rely too heavily, or "anchor," on one trait or piece of information when making decisions." A buyer or renter may hang onto one of the first bits of intel about a place—say, a broker points out that a unit is the only renovated one in a building—and somehow that becomes the most significant characteristic by which to evaluate the apartment, making it the so-called "anchor," and proceeds to compare everything else in the building against it when, perhaps, that may not be as important a deal-maker (or breaker) as it may seem.

This may be a consequence of how memory is formed, says Burnett. "You have a lot of information to take in from the world around us, and [the brain] does this on the fly. It's got a lot to do and little time to do it. So it builds a mental map of the world as we know it, and all our memories and associations with it," and anything new will figure prominently, he says. "That's why first impressions are so important...If you are going to a new apartment, and already you're in this really emotional, highly stressed state because you don't really want to move, you know it's going to be a hassle, it's a big decision to make, so the first experience you have is going to be the most potent one." So someone screaming in front of the building the day you visit might stick with you far more vividly than anything else.

Illustration courtesy of RentCafe.

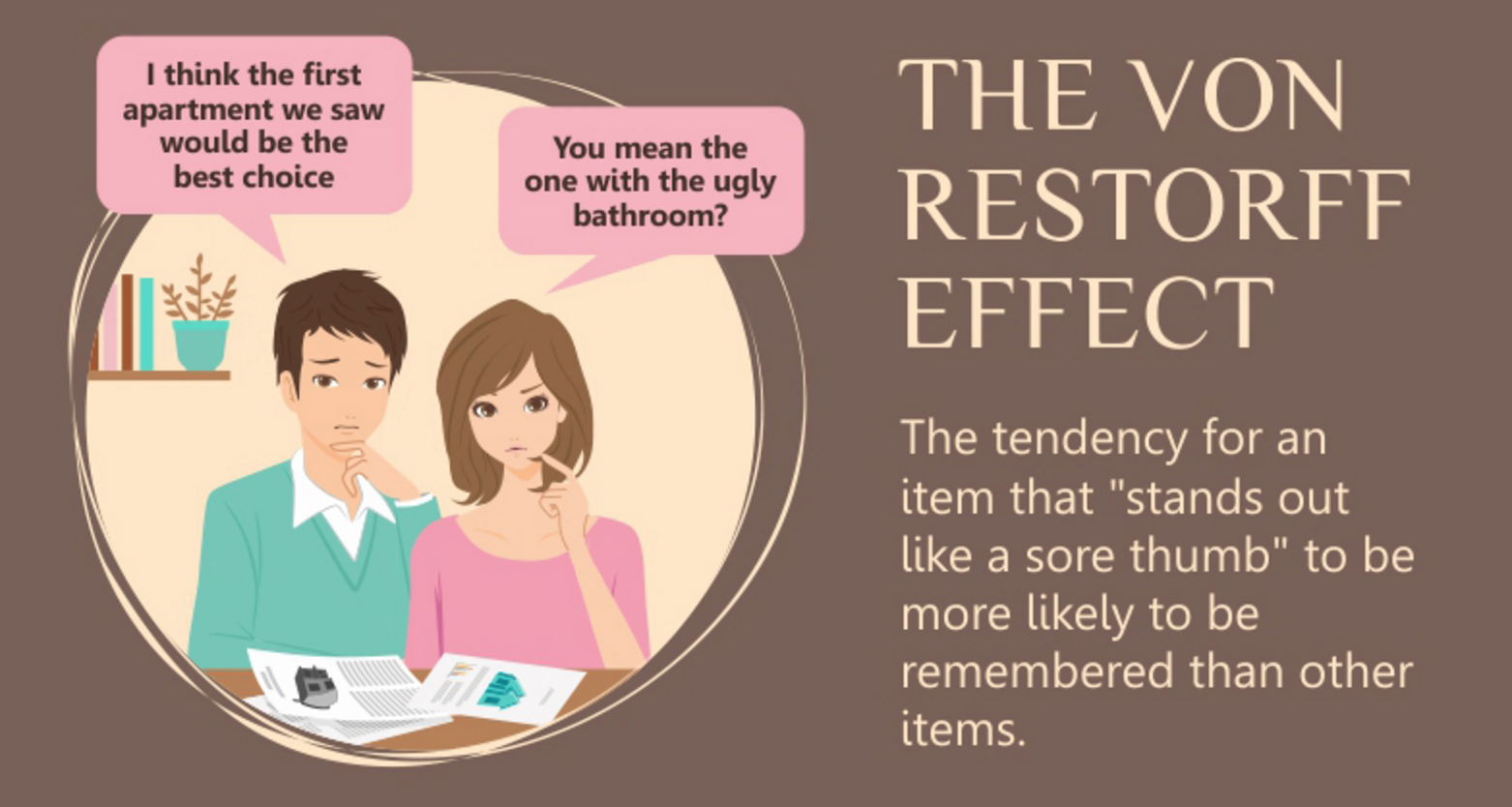

Von Restorff effect

With this bias in play, a turn-off becomes a deal-breaker, perhaps even when it shouldn't, either because it's easily solved or isn't as problematic as it may seem. For instance, a renter may walk away from an apartment with too-few closets but has everything else going for it, never mind that a trip to IKEA for inexpensive dressers could quickly solve the problem.

Illustration courtesy of RentCafe.

So what's the antidote then? Information, for starters, says Burnett. "If you want to break up with your [current] environment and find something new, it needs to be explained to you a lot more thoroughly why it's a good idea before you take a leap. Your brain needs to be sort of cajoled before embracing such a big decision."

Consider checking out a space numerous times, too, rather than relying on one visit. "You need to have a lot more experiences with a place before you override the first impressions," he says.

You Might Also Like