Pirates, glue factories, and mob graves: Blissville is Queens's dumping ground

Blissville was once a hub of noxious industry. Now it's somewhat less bustling, and somewhat less noxious, but still home to light industry and next to an aquatic Superfund site.

Marjorie Cohen

Blissville, a slice of Long Island City bordered by Calvary Cemetery, the Long Island Expressway, and Newtown Creek, is a rough-hewn, mostly forgotten outpost of New York City.

Once a bustling industrial hub, most of Blissville today is occupied by warehouses, auto repair shops, and yes, there are still some factories. There is also a light sprinkling of homes and storefronts, and much of the building stock dates back to the 19th century. Calvary Cemetery looms along the length of Greenpoint Avenue, the main drag of the neighborhood. The walls surrounding the cemetery, and some of the nearby streets, are littered with broken bottles and other trash, giving today's Blissville an unloved look. The gated cemetery is the only swath of green in the neighborhood—there are no parks or playgrounds.

In the neighborhood’s odiferous glory days in the 19th century, its location on the banks of Newtown Creek is what made Blissville a place to know. By the 1850s, the creek’s banks were lined with glue factories, smelting and fat-rendering plants, refineries, foundries, and other heavy industries, connected to the rest of the country by trains that ran through the area. Now, not coincidentally, the creek is among the most polluted bodies of water in the country.

Bob Singleton, executive director of the Greater Astoria Historical Society (in spite of its name, a group that documents the history of more of Queens than just Astoria) says that he doesn’t know “of any other waterway that has as much history as the Newtown Creek.”

In the 1600s the area was said to be a center for piracy, home to some of the folks who sailed with Captain Kidd. Legend has it that one of Kidd’s friends let him stash some of his plunder in the area. According to a study of Newtown Creek by a group of Columbia University graduate students, Peter Stuyvesant couldn't persuade anyone in New Amsterdam to settle in the area in the mid 1600s. By the 1700s farms were being established and settlements began to appear. The land that is now the cemetery was once a prosperous tobacco plantation.

But, that was then. Twenty-first century Blissville is now largely unknown and ignored, even by those who live in the nearby neighborhoods of Long Island City and Greenpoint.

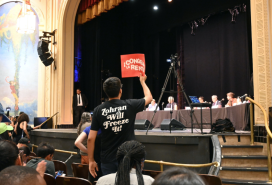

When Miguel Cavanzos, who lived in Blissville for five years, went before Community Board 2 (which includes Blissville) in 2015 to petition for a public park in the area, he asked how many people in the room had heard of Blissville.

“Only one person raised his hand,” said Cavanzos. The neighborhood, he says, is “a diamond in the rough with a rich history that is yet to be discovered.”

Blissville was named for the same man who established Greenpoint, just across Newtown Creek

In the 1830s and 40s Neziah Bliss, a forward-thinking businessman and industrialist, bought up much of the land that is now Greenpoint and Blissville. Much of Bliss’s commercial success can be traced back to the early 1800’s when he began a fortuitous friendship with Robert Fulton, the man who, although he did not invent the steamboat, was responsible for making it a commercially successful means of travel.

Born poor in Connecticut, Bliss became one of the wealthiest men in New York, establishing Novelty Iron Works, the source of the engines that powered most of the vessels built in New York. Marrying into one of the wealthiest Dutch families in New York—the Meseroles—only elevated his status.

Bliss laid out the streets of Greenpoint, which are just across Newtown Creek from Blissville, anticipating the boom that would eventually hit the area. According to a History of Long Island written in 1902, “he at once saw that the territory offered great chances for him and threw himself into [developing] it with characteristic energy and promptitude.” The financial panic of 1837 delayed his plans, but eventually his gamble paid off, and when he died in 1876 he was a very rich man.

Not surprisingly, Bliss chose the finest street in Greenpoint—Kent Street—for his own home, located at #130. Although the house is “one of the finest examples of the Italianate style remaining in Greenpoint today," according to local historian Geoff Cobb, there is no plaque to identify it.

“Nor is there any mention in any local place of the man who helped start [the] community,” Cobb writes on Greenpointers.

Bliss also built the first version of what was originally called the Blissville Bridge, today’s Greenpoint Avenue Bridge, linking the Brooklyn and Queens portions of his empire. Besides Blissville, Bliss’s name endures at the 7 train’s 46th Street-Bliss Street station in Sunnyside. (Bliss laid out some of Sunnyside as well).

When Catholics ran out of room to bury their dead in Manhattan, they ferried them over to Blissville

By the middle of the 19th century, Manhattan was running out of cemetery space, so the Roman Catholic church bought a parcel of land in Blissville, land once farmed by Richard Alsop's family. Founded by the first archbishop of New York City, “Dagger John” Hughes (nicknamed because he seemed to be “more a Roman gladiator than a follower of the meek founder of Christianity, according to a fact sheet from the Catholic Heritage Curricula), the cemetery began as a no-nonsense place for burials. It was never meant to be a park-like cemetery like Green-Wood in Brooklyn or Woodlawn in the Bronx.

Plots cost $7 and according to Forgotten New York, the bereaved often dug the graves themselves. Bodies were ferried from Manhattan across the East River and down Newtown Creek. By 1850 there were as many as 50 burials a day, many because of recurring cholera epidemics.

Mitch Waxman, an expert on all things Newtown Creek-related, is leading a walking tour of the cemetery in December.

The cemetery is a popular movie and television location: Bruce Wayne’s parents and Spiderman’s Uncle Ben are buried there, and it is the final cinematic resting place of Vito Corleone.

Some real people buried in the cemetery are Annie Moore, the first immigrant to pass through Ellis Island; songwriter Joe Howard (“I Wonder Who’s Kissing her Now”); Mafia “Boss of Bosses” Joe Masseria; Tess Gardella, a white actress who played Aunt Jemima in Showboat in 1920; Al Smith, the first major party candidate for president who was Catholic (he lost to Hoover); and Robert Wagner III, mayor of New York from 1954-1965. The 1718 stone of Richard Alsop, the original owner of the land, is the oldest in the cemetery.

Blissville is a 'hidden town,' but there are some notable businesses

Cavanzos loves Blissville and describes it as a “hidden town.” It's quiet and peaceful after the trucks have left the area and the businesses close for the day, giving the residents the place to themselves. He doesn’t mind the lack of a laundromat or a supermarket or cafes, but what he does wish for is a park for the children of the neighborhood to play. A few years ago he presented a petition to the community board asking for help converting a vacant triangle of land into a park. So far nothing has happened.

Mitch Waxman often writes about Blissville at the Newtown Pentacle, and jokingly refers to it as DUGABO: Down Under the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge. He says he likes to “stay ahead of the real estate guys on this sort of thing.”

The most imposing building in Blissville is The City View on Greenpoint Avenue. Built in 1905, it now functions as both a hotel and a homeless shelter. Once the home of PS 80 and the most imposing structure in the neighborhood, it has never been landmarked.

One of the standout businesses in the neighborhood is Silvercup Studios East. Ugly Betty, Elementary, and Person of Interest were all filmed there. The complex (one of Silvercup’s three locations) encompasses six drive-in studios designed to replicate a Hollywood movie lot.

A slightly less imposing business, but one that embraces the Blissville tag on its website, is Colbar Art. Since 1995 the company has been casting, mold making, model making, and engraving, and it claims to be the largest manufacturer of Statue of Liberty models in the world.

In 1989 Hank Linhart walked through Blissville. He liked it so much he made a movie

Media artist Hank Linhart made a feature-length film, Blissville: An Investigation, which he describes as a “docu/poem.”

It is “sort of about looking at the overlooked places, and the overlooked history of places,” Linhart says. “It’s also about looking at places that you drive through and you don’t think anything of.”

In the film, Linhart interviews past and present residents of the neighborhood and tells the story of a settlement made up of people from Rome that once thrived nearby but was, according to one resident quoted in the film, dismantled by Robert Moses at the time of the World’s Fair.

Want to live in Blissville? Go there first

Cavanzos found his Blissville apartment when he drove through the neighborhood and saw a “For Rent” sign. He parked, found the owner of the place, negotiated the rent, and moved in. For the rest of us, we may be luckier with listings.

There is one apartment in Blissville online now, though the listing says it's in Sunnyside. The one-bedroom railroad apartment in a 12-unit rent-stabilized building is asking $1,500. The entire building was sold five years ago for $1.15 million.

Unlike other parts of Long Island City, Blissville is not a place where new residential developments are likely to be built any time soon; the zoning rules don’t allow it. But if you’d like to live not too far from Blissville, you can buy a one-bedroom, one-bath condo with a balcony, a washer-dryer, and an open kitchen for $880,000 nearby in Hunters Point.

You Might Also Like