Getting a real estate start in NYC: Do today's transplants really have it easier?

To many longtime New Yorkers—the ones who scrambled for years to pay the rent for cramped apartments with indifferent landlords—the Millennial generation seems to have things awfully easy. Newcomers nowadays arrive, the narrative goes, in a city scrubbed of the crime it was once was notorious for, and—with mom and dad’s support—move into swanky spaces in the hottest neighborhoods. The most fortunate members of this cohort are set to inherit unprecedented wealth from their Boomer parents, purchase prime Manhattan real estate, and turn NYC into even more of a “luxury city,” according to an article in the Daily Beast.

Gothamist’s Brunch Hate Reads series is devoted to stories about this kind of young person; one article that provoked significant ire chronicled a 22-year-old’s move into a $3,700 a month Bleecker Street co-op. But isn’t starting a life in New York about the hustle? How do the experiences of Millennial newcomers compare to those of older New Yorkers?

As a Millennial myself—I was born in 1983, at the early end of this supposedly most “entitled, needy, and self-centered” generation—the experiences of the much-maligned “trustafarians” don’t mirror mine nor those of my friends. New York has always been expensive, but many of us graduated college into a new Gilded Age, with skyrocketing rents and even fewer options for young people of ordinary origins looking to get started in the city.

Of course, establishing oneself in New York has always required a little ingenuity—and luck. Vica Miller, a writer, producer, and literary salon hostess, remembers coming to the city from her hometown of St. Petersburg (then Leningrad) in 1990 and crashing with a series of friends as she figured out her next move. “The situation in Russia was dire at the time, and my family suggested that I try to ‘stick around,’” she says. “How does one do that, with no money, no work permit, and no lodging?”

By chance, Miller spotted an ad in the New York Times from someone seeking an au pair for his two dogs. The dog owner turned out to live in a midtown penthouse apartment, and after she nailed the interview, Miller moved into the maid’s quarters, where she lived for the next two years. “He treated me like a daughter,” Miller says of her employer. “It helped me to find my grounding in New York City.”

This kind of serendipity seems almost quaint now: It’s likely harder to find a quirky mentor of means when many of New York’s luxury apartments lie vacant, their owners globetrotting billionaires using them as pieds-a-terre.

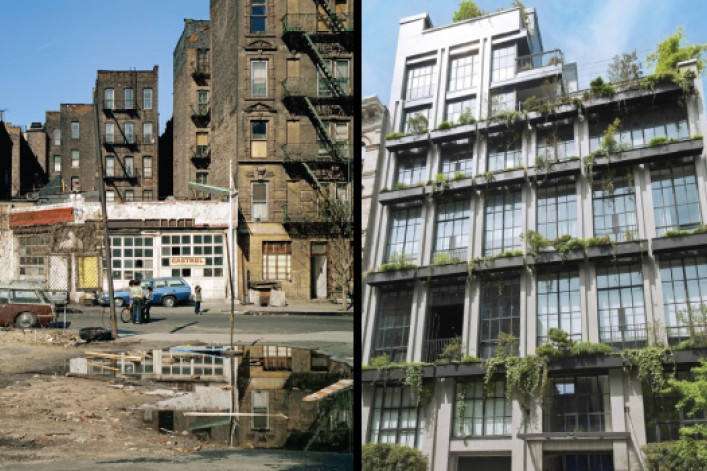

Rachel Kahan, who came to the city in 1996 to work in publishing, moved into much rougher digs than Miller. Her tiny, 7-foot-by-10-foot bedroom, created by dividing a larger room in two, was in a mice-ridden apartment in the heart of pre-gentrification Williamsburg, at the time “an open-air drug and prostitution market,” she remembers.

She was making a meager editorial assistant salary, but “was pretty determined to go it alone.” Eventually, she relocated to a one-bedroom in Astoria with far fewer mice. “I have always lived in the outer boroughs, first out of economic necessity and then because I love them, but the days of significantly cheaper living there is over,” Kahan observes.

Her younger brother, a Millennial, has had a much different experience: with a larger starting salary, he was able to move into a NoLiTa apartment—albeit one shared with three roommates. But perhaps the most major distinction, Kahan says, has to do with health insurance. Thanks to the Affordable Care Act, people under 26 can stay on their parents’ plans—which means they don’t have to take a job just to get health coverage. “I stayed in at least one job I should have quit because of insurance,” Kahan says. Her brother, on the other hand, was able to remain unemployed by choice while job-hunting—a luxury previous generations were not afforded, and which perhaps allows Millennials the time to find more lucrative gigs.

Even so, income isn’t keeping up with rising rents, and the number of affordable neighborhoods in New York are dwindling. I live in Astoria, a neighborhood I chose not only for its fantastic food and friendly, small-town vibe, plus plentiful neighbors my age, but also for its relatively reasonable rents. Now I watch with dread as the media hails the ascent of Queens, leading to a glut of newcomers and the attendant jump in housing costs.

Studies show that Millennials are three times as likely to receive support from their folks as their own parents were from theirs; perhaps this is why the generation has been deemed entitled. But is it really so easy for Millennials? What factors into the decision to accept cash from family?

Marisa Pisano was an 18-year-old trying to launch a dance career when she moved to New York in 2005. Her parents agreed to help pay the rent on a studio at 74th and Broadway, close to Lincoln Center and her dance classes. She certainly was no slacker: Pisano got a job as a bartender and waitress, and gradually began taking over most of her expenses. Though she loved the apartment—and her kindhearted landlord, who once helped her catch a mouse at 2 am—she eventually moved out to save money.

Pisano acknowledges that some of her peers may be saddled with a sense of entitlement, but their financial dependence may not totally be their fault. “The economy they're growing up in makes it hard to reap the benefits of hard work,” she says. “Nowadays, you can go to a good school but not get a good job.”

Indeed, stagnant wages and the burden of student loan debt keep Millennials from attaining the same milestones their parents did. Millennials are better educated but poorer than Baby Boomers, taking home $2,000 less than their mothers and fathers earned at the same age. And as Kahan points out, young people looking to relocate to New York will find far fewer affordable neighborhoods these days, even in what used to be relatively cheaper locations like Queens. Perhaps this is the reason many young people are bidding “goodbye to all that” and leaving the city for greener (and cheaper) pastures.

Kate Acuna, who moved to New York from Virginia at 23, adds that another challenge is that it’s nearly impossible to get on an apartment lease if you have no work history and can’t prove you’ll pay rent. “Most people I talked to didn’t want to take a chance on a jobless gal,” she recalls. Without parents able to sign on as guarantors, she had to lie in order to get a broker to “trust” that she’d pay up—and then she cobbled together a number of odd jobs to make ends meet. Many of Acuna’s friends, on the other hand, had help from family when they moved to big cities. [Editor's note: We've got great suggestions for workarounds if you don't have a guarantor.]

Miller agrees that it’s trickier to navigate the rental market now: “There are people in their 40s who are still living with roommates, because the rent is so horrendous.” But there’s no shame, she says, in accepting financial help when it’s offered.

Many New Yorkers love to share war stories, and it’s a point of pride to have faced down the city’s particular challenges—be it crime, crooked landlords, or rodent infestations—and live to tell the tale. The question of which generation had it hardest is subjective, but it’s clear that living here is hardly a breeze for Millennials. Vica Miller says that the solution may be adopting a more neighborly approach.

“In American culture, everyone is so conditioned to be an individualist and do everything on their own,” she says, and people end up feeling like failures when they need support. New Yorkers should remember that they’re part of a community, Miller says. “It’s okay to ask for help.”

Related:

5 ways renting in the city is unlike anywhere else

10 commandments of an NYC rental search

The 8 best NYC neighborhoods for first-time buyers