3 New Yorkers on how they cope with nonstop noise

iStock

Jackhammers, whining saws, backup alarms and the ka-chunk of dump trucks dropping their loads. Welcome to New York City under construction.

With construction noise ranking as the most common type of noise complaint among New Yorkers, and heavy machinery seemingly running on every block, we asked a few residents living in construction zones how they cope.

Here’s what they had to say.

Seeking a quieter SoHo

A commercial photo retoucher with a home studio in the SoHo co-op where she's lived since since 1998, Kellie Kulton lives across the street from a firehouse and a park frequented by loud people at all hours. Her long-term beef, though, is with the construction surrounding her, from infrastructure projects to sidewalk installations and now, a rehab of the park.

"I would wake [up] because my apartment was shaking during a water-pipe replacement and repaving project," she says. There was "unbelievable noise" one night after 10 p.m., and she looked down from her fourth-floor window to see a giant jackhammer mounted on a vehicle driving up the sidewalk—it was a nighttime project to dig up a bus stop and replace it with an interactive bus kiosk. Here's a sample of what that was like, filmed at 11:45 p.m.:

Note: Technically speaking, construction in the city is only allowed to happen between 7 a.m. and 6 p.m. on weekdays. But according to the city noise code, "Alterations or repairs to existing one- or two-family, owner occupied dwellings, or convents or rectories, may be performed on Saturdays and Sundays between 10:00 am and 4:00 pm if the dwelling is located more than 300 feet from a house of worship." Also, after-hours and weekend work can take place "with express authorization from the Departments of Buildings and Transportation. A noise mitigation plan must be in place before any authorization is granted." Apparently authorization is granted a lot in SoHo.

"That kind of project happens frequently in the neighborhood without public notice,” Kulton says. "Any way you cut it, the amount of construction and the noise associated with it… it’s nonstop [and] enough to drive you insane."

As a former president of her co-op board, she knew her way around the city’s complaint systems, but said calling 311 and even sending video to a local news station yielded no response.

In the end, because she likes her apartment and location, she does what many do: stuffs her ears, insulates best she can—her building replaced its windows—and finds other distractions.

“I stay out of the city as much as possible. I close all windows. In the summer I run my A/C to shut out the noise," she says. "In the winter I have a white-noise machine. I block out the noise with other noise."

She adds, “There’s a trade-off for everything in New York, so you have to decide what you’re willing to trade.”

Wild West Village

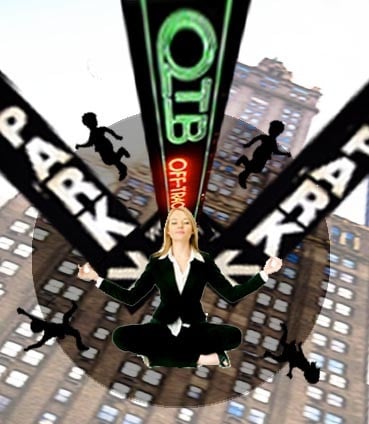

Lauren Mowery too has a variety of noises coming through her apartment walls—insomniac and music-playing neighbors among them—but it’s the feeling of being inside a circle of construction that keeps her from enjoying the quiet of her home in the far West Village. Her misery is compounded by the fact that, as a freelance writer, she works from home. She and her husband bought their Bank Street apartment 10 years ago, expecting nothing "beyond general New York City noise."

Between private home renovations, street repairs, and new development, she says, "The West Village has been under construction for years... There’s always something I can hear from my living room."

And the construction noise is like surround sound. Mowery estimates that about 80 percent of the streets in a five-block radius around her are torn up, which she has documented in photos on her daily walks with her dog.

“It’s like living in a construction site 24/7," she says. "The streets are ripped up for pipe replacements. Trucks are rumbling down the street all the time. We’re on a narrow street, and if one truck stops, cars are laying on their horns and that makes you crazy.”

She hasn't filed formal complaints with the city. Instead, she says, "We just suffer in silence."

As a travel and wine writer, she travels as much as possible to escape the noise, but concedes, "That’s not a long-term solution." Nor is camping out at cafes, which have started to limit laptop users’ time.

When at home, she practices meditation and yoga to relieve the tension of her environment, and wears headphones day and night.

Like her neighborhood, she says her methodology is "a work in progress."

“There are so many sources and they’re so diffuse, you can’t blame any one thing," she says, adding, "It’s city life."

Figuring it out in Forest Hills

Few outsiders would peg the leafy neighborhood of Forest Hills as a hotbed of noisy construction. Public relations executive Beth Cotenoff didn't when she moved there 10 years ago. But her otherwise peaceful home became a nightmare when buildings near her were razed and construction on new buildings started in 2015. It hasn't stopped since.

Cotenoff’s corner apartment on 72nd Road and Austin Road was particularly exposed to construction.

"Basically I was surrounded," she says.

The view out the window of Beth Cotenoff's Forest Hills apartment

"Waking up every day to noise is stressful," she says, adding that frequent weekend work gave her no reprieve.

"They had a special permit, and not knowing when they were working on weekends was also an underlying stress, leaving [me] unable to really plan for anything," she says.

Here's a short sample of what she had to deal with:

Cotenoff filed complaints, took video and pictures, including of night and weekend construction, and took to social media, to no avail.

"I got some 'duly noted' responses from the city’s DOB," she says. But with on and off disruptions in work, she couldn't tell if her complaints had registered.

According to city protocol, an inspector should have been sent out to check on the problem. It's unclear if that happened.

“I don’t know if it did anything, but making my voice known made me feel a teeny bit better," Cotenoff says.

Inspectors often respond to calls days or even longer than a week after a call, meaning they may not catch a corner-cutting contractor in action. Also, if a contractor has a special permit and is within the bounds of the noise code, there may be nothing an inspector can do.

The last straw came when construction got close to the lot line on her side of the building, her building management sent letters advising tenants to remove their air conditioners, and the window was permanently sealed. She embarked on an apartment search and two weeks later, negotiated out of her lease, then moved to Washington Heights

Her advice: "Be aware and look around to see the conditions of the buildings next to you. If something is decrepit, they’ll likely tear it down."

We'd add that you should consult the zoning map for your neighborhood and try to figure out if the buildings around you are the biggest allowed. If not, they might come down one day to make way for something taller.

You Might Also Like