Five residential buildings with fascinating past lives

Scrape away at almost any old building in NYC and you’ll find layers of history. The city’s many incarnations are visible in the fading signs on the sides of buildings, in rediscovered old burial grounds, or in odd architectural remnants in apartments. And in fact, many of the city’s residential buildings began as something else entirely—read on to learn about the co-ops and condos with fascinating past lives.

The Octagon

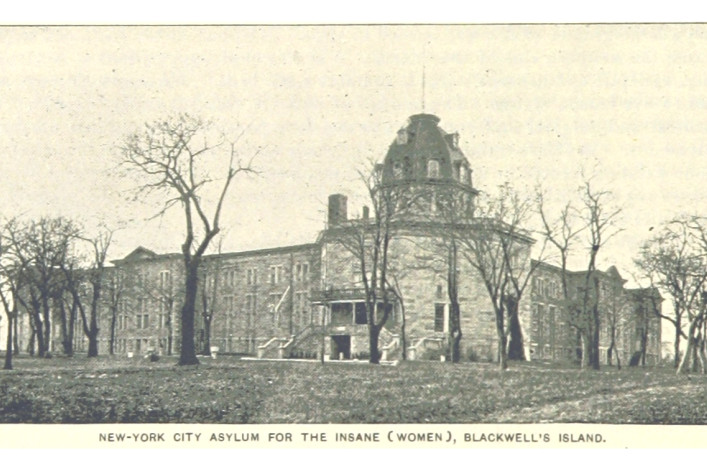

Before it was Roosevelt Island, the little strip of land in the East River between Queens and Manhattan was known as Blackwell’s Island, and it was a much grimmer spot: The area was where the city sent its undesirables, and was home to a prison, an asylum, and a smallpox hospital. The mental hospital, known as Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum, was the first of its kind in New York; per Asylum Projects, after similar facilities were built, it was devoted primarily to immigrants believed to be mentally ill.

In 1887, the New York World journalist Nellie Bly was asked by her editor, Joseph Pulitzer, to feign mental illness, get committed to the asylum, and report back on the conditions there. She discovered that the patients—many of whom were not ill at all—lived under inhumane and abusive conditions; you can read her essay on the experience here. After Pulitzer helped secure her release and the report was published, the city devoted an additional $1 million to its Department of Public Charities and Corrections, and ultimately the hospital was shut down.

In the 1950s, the building was demolished save for its entrance, known as the Octagon for its distinctive shape. It then sat vacant for decades, until 2006, when it was renovated and expanded with an addition. Today, the LEED- certified apartment complex is home to 500 rentals with floor-to-ceiling views of the Manhattan skyline.

Rutherford Place

305 Second Avenue, also known as Rutherford Place, is home to 127 luxury duplex and triplex apartments with high ceilings, views of Stuyvesant Park, and access to upscale amenities like valet service and a rooftop sun deck. A number of celebrities, including Sean Combs, Tom Cruise, and Mimi Rogers, have called the property home, per New York Magazine. But the building’s origins are somewhat less glamorous; originally known as The Society for Lying-In Hospital, it once served as a maternity hospital.

Built in 1902, the facility was a gift to the city from J.P. Morgan and designed by famed American architect Robert Henderson Robertson. In an article about the property, the New York Times notes that the hospital was once believed to have been home to 60 percent of all Manhattan-based births.

After 1934, when the maternity hospital moved, the property then housed other medical facilities, including the Manhattan General Hospital and, later, a drug treatment center. Fifty years later, Orb Development took over and converted the Renaissance Revival building to expansive, high-ceilinged apartment units—though hints of its origins remain in the sculptures of swaddled infants embedded in its façade.

The Forward Building

In the Two Bridges neighborhood of the Lower East Side, right beside Seward Park, sits the Forward Building, a condominium property with a Beaux Arts façade. When it was renovated in 2006, the building was at the forefront of a residential development boom in the area, but it began its life as something very different: the home of a newspaper.

Though it’s hard to imagine a newspaper commanding an entire building in this digital media era, in its heyday, the Jewish Daily Forward was a powerful publication. It was founded in 1897 as a socialist, Yiddish-language paper, and when the Forward Building went up at 175 East Broadway in 1912, it had a circulation of 120,000—impressive for the time.

The Forward continued to flourish throughout the 1920s, according to this Times piece, at the same time as new Jewish immigrants were arriving on American shores, and older ones were moving up in society. Circulation fell in the following decades as immigration dipped; the paper sold the building and moved uptown in 1974.

Reflecting the changing demographics of the neighborhood, the Forward Building was converted to a Chinese church by the Lau family, who later decided to convert it into condos. The plan fell through until architect Ron Castellano stepped in for a redesign in 2006. Now, residents enjoy upscale, contemporary digs, and proximity to hotspots like Mission Chinese Food.

The Forward is still around, though; just last week, it published a look back at its former home, noting that its socialist roots are evident in the busts of Karl Marx and Frederich Engels that look down from its edifice.

The Ansonia

The Ansonia has gone through several incarnations within its ornate and dramatic walls. The Upper West Side condominium building got its start as a residential hotel where many New York luminaries hung their hats, and in later years, attracted plenty of controversy for its salacious basement activities.

The man behind the building, William Earl Dodge Stokes, was the heir to his family’s prosperous mining business, and a celebrated developer in his own right. With architect Paul E. Duboy, he built the Ansonia in 1903; as this in-depth essay from Curbed reveals, the hotel was lavish from the start, offering its residents perks ranging from Turkish baths to fine dining. Stokes was also something of an eccentric: he married multiple times, was shot by a lover, and installed an illegal farm on the roof of the hotel.

The building also invited scandal. The Chicago White Sox’s scheme to throw the World Series was supposedly plotted in one of the player’s rooms, but the hotel really went downhill with the advent of the Great Depression, when Stokes’ son could no longer fill its rooms. In the 1960s, then-owner Jake Starr resorted to renting out the basement to pay the bills, and the first tenant was the Continental Baths, a gay bathhouse where everyone from the New York Dolls to Bette Midler performed. The baths were raided by police, and converted to a straight swingers’ club called Plato’s Retreat in 1977. During the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, then-Mayor Koch shut down all of the city’s bathhouses.

In 1992, the building was converted to 425 apartments offering a wide range of floor plans and layouts; today a condo there is worth millions, a return to the building’s grand origins.

455 Central Park West

Today, 455 Central Park West (known as 455 CPW) is home to condos and rentals, as well as a gym and a pool, but the Manhattanville building with the gothic appearance got its start as a cancer hospital where new radiation treatments were explored.

Built in 1884, the hospital was the first of its kind, per a Times article; back then, cancer was considered a baffling and shameful disease. The building was also renowned for its creative layouts. 455 CPW’s signature rounded towers used to be the hospital wards, designed so that doctors and nurses could make observations from a central vantage point.

In the early 20th century, when the benefits of radiation were being uncovered, the hospital’s doctors developed new methods in the use of X-rays, and procured four grams of radium for further study. However, during the infancy of this treatment, the negative side effects of radiation were poorly understood, and many patients were damaged more than helped. So many died within the hospital’s walls that the facility added its own crematorium.

Interestingly, the hospital relocated and later became part of Memorial Sloan-Kettering, today ranked as the country’s top cancer center. Within the castle, though, conditions remained poor; the building became a nursing home that was later accused of neglecting its residents.

In 2000, 455 CPW was converted into a luxury residence, and many of its apartments are in the former wards and feature unique, circular interiors. But New Yorkers haven’t forgotten that there was once a crematorium on the premises, and according to Curbed, many believe the place to be haunted.

You Might Also Like