- A new city proposal would allow drone operators to apply for flights 30 days in advance

- Drones could save buildings money by detecting problems early and eliminating scaffolding

- Shift comes after city settled a lawsuit with a Brooklyn aerial cinematography company

A drone hovers near a 25-story brick building to take high-resolution images that experts will examine for facade defects.

AeroSpect

In a move that could be a boon to condo and co-op boards, New York City has proposed regulations to make unmanned aircrafts legal, paving the way for more widespread use of drones in building facade inspections.

After years of urging the public to call 911 on drones, the city’s major shift comes the day after it settled a 2021 lawsuit filed by Xizmo Media Productions, a Brooklyn-based company that specializes in aerial cinematography. The city agreed to a temporary permitting process for the company’s film and media jobs until new rules are adopted.

“As drones have been increasingly used to film stunning cinematic videos, support first responder rescue efforts, aid in research projects, and conduct surveys, it is clear that the city must balance the ever present safety and privacy concerns inherent in widespread drone use against the important gains that may result from this new technology,” according to the proposed, citywide regulations, published Tuesday in the City Record.

Drones are being used in building facade inspections mandated by NYC, but whether they’re legal to fly in the five boroughs has been a tug of war for years.

Supporters of the new technology, including several engineering firms, say these flying bots can save buildings money by detecting problems early and cut the need for unsightly scaffolding.

“Drones are used all the time in innovative ways all over the place across the country,” said Bill Murray, vice president of the metro area for the American Council of Engineering Companies of New York, a coalition that supports the regulated use of drones. “New York City is unique obviously because it’s congested and dense. It makes many projects and many technologies require a greater level of thoughtfulness and more careful regulations.”

A major shift in favor of drones

For years, some city officials had feared drones were unsafe in a dense city. What stymies widespread implementation of drone use here is a 1948 city law that bars aircraft takeoffs and landings outside places designated by the Port Authority and the transportation department.

But Xizmo argued that the Federal Aviation Administration governs airspace, preempts city law and approved applications for each of its drone flights.

The settlement is a landmark victory that opens the way not just for drone-aided facade inspections but also drone light shows, real estate marketing, flyovers for movies and other jobs, says Edward Kostakis, Xizmo co-founder, who has conducted drone-aided facade inspections in the city with his other business, AeroSpect.

He predicts legalizing drones would help the city solve rather than create problems, including cutting the need for scaffolding and finding facade issues before they endanger pedestrians.

“We can send a drone anywhere and do anything and solve a lot of the city’s problems in way less time with way less money,” Kostakis says.

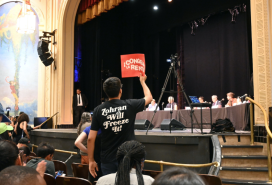

A hearing on the proposed permitting process has been scheduled for 10 a.m. July 7th in the auditorium of 1 Police Plaza.

The plan calls for applications for flights of unmanned aircraft to be submitted to the New York City Police Department 30 days in advance. Applicants would have to file information that’s similar to a flight plan, with time and location, along with proof of insurance, copies of the company’s cybersecurity and privacy policies and the FAA registration certificate for the aircraft and the pilot.

Drone operators would also have to notify the local community board and post notices in areas where they anticipate capturing images and audio.

The application fee would be $150. Penalties for violations range from $250 to $1,000.

“This settlement was in the best interest of all parties,” the city law department said in a brief comment.

The buzz on drones and how they work

St. Patrick’s Cathedral has done it, and so have the super skinny skyscraper known as Steinway Tower by Central Park and Brooklyn Technical High School, according to companies involved.

The demand for drone-aided facade inspections has doubled in the last several years, says Joshua White, owner of Queens-based Aerial VP, which conducted one of the first such inspections, at Brooklyn Tech, nine years ago.

White and others say the demand has been fueled by the city’s latest incarnation of the Facade Inspection and Safety Program (FISP), also known as Local Law 11, which in 2020 began requiring inspections every five years of buildings more than six stories high.

From below, the unmanned aircraft can look like an insect with four legs jutting out as it buzzes systematically up and down or across, about two feet away from the building facade. It can record video or snap thousands of high-resolution images, which are stitched together. Engineers and other professionals then examine details to look for defects.

Some drones offer thermal imaging to detect energy leakage from the building and LIDAR, or light detection and ranging, to create 3D images. Software companies, such as Manhattan-based T2D2, use artificial intelligence and thousands of images of facade defects to pinpoint and analyze problems on drone photos.

Usually, drone services are tapped by engineers and architects hired by co-op and condo boards, building owners and management companies.

Traditionally, the first step in most facade inspections is done at street level, with engineers and other professionals using binoculars and cameras. They can then get close up to problem areas by dropping down from the roof with rigging, using a portable boom or bucket lift or setting up scaffolding.

Should your building use a drone for facade inspections?

Beyond the city law, deciding whether to use drones can be complicated, experts say.

“Not every building can be scanned by a drone,” White says.

Dense, tall buildings in Manhattan often block GPS signals, which are used to guide the drones, White and Kostakis say. That requires drones to be flown manually, they said, so building owners and professionals need to make sure they hire an FAA-certified, experienced operator who can avoid signs and other obstacles.

Safety and privacy are also considerations. To protect pedestrians, a sidewalk shed might have to be erected, drone operators say. Residents who don’t want to be caught on drone cameras would have to be alerted in advance by building’s owners and management of an incoming drone, experts advocate.

Another big factor is estimating cost effectiveness.

The drone bill can be $5,000 and up, depending on extras such as thermal imaging and the size of the building, but scaffolding for just one side of a building can hit $7,000 or more, according to architect Giulia Alimonti, president of the metro New York chapter of the International Institute of Building Enclosure Consultants.

“Let’s say we fly the drone and we see there’s a crack in the wall,” the architect says. “Then we know exactly where to do the scaffolding section and where to do the probes. We’re not doing it at random.”

Bill Payne, president of Payne Engineering in Fort Lee, New Jersey, who has used drones outside of NYC, said drone companies tend to “oversell.”

He finds ground-level visual inspections with binoculars effective in catching most problems and questions how much value a drone would add. Thermal imaging and 3D services would add crucial information, he said, but that would raise costs.

On top of that, humans will still need to analyze results and comply with hands-on, close-up examinations required by FISP, Payne notes.

“If a facade study is $10,000 and the design for facade repair is $10,000 to $20,000 and your $2,000 to $5,000, sometimes $9,000, is for the drone study—that becomes such a significant portion of the fee, it’s not an easy, easy sell,” he says.

Further study needed on drone pros and cons

Less than two years ago, the NYC's Department of Buildings issued an 82-page report calling for more study on the use of drones to comply with FISP.

Drones can offer an “enhanced visual inspection” to the usual ground-based inspections, but they could be especially helpful in larger buildings and spots with difficult angles, the report says.

In what may be the only point in the debate that all parties agree with, the report’s authors concluded that drones cannot fulfill all FISP requirements and replace professionals. For example, FISP requires certain examinations at least every 60 feet, including “sounding” or tapping the facade to hear for any voids behind it.

Bill would test drone effectiveness for facade inspections

A pending bill before the City Council could help building owners decide if a drone will be in their best interests.

The legislation, introduced by Councilman Keith Powers, would follow up on the DOB recommendation to run a pilot program for at least one year to drill down into the pros and cons of drones.

That includes whether they’re more effective for certain building materials, such as glass versus terracotta; if they’re better at detecting certain defects, such as cracks versus bulges; and if they’re more appropriate for high-rises than smaller buildings.

You Might Also Like

Sign Up for our Boards & Buildings Newsletter (Coming Soon!)

Thank you for your interest in our newsletter. You have been successfully added to our mailing list and will receive it when it becomes available.