Edward Norton’s ‘Motherless Brooklyn’ recalls how Robert Moses reshaped NYC in his own image

“Motherless Brooklyn," which stars Edward Norton, right, features a major real estate villain modeled on Robert Moses, who is played by Alec Baldwin.

In “Motherless Brooklyn,” writer, producer, director, and star Edward Norton transplants the action from the original 1990’s Brooklyn setting of author Jonathan Lethem’s book to 1950’s Brooklyn. In Norton’s version of Brooklyn, the men wear hats, women dress up to go to work, and cars have tail fins. But all is not as placid as it seems.

The shift in setting allows Norton to include a major real estate villain, a master builder, and bully intent on reshaping New York City to fulfill his own singular vision, who is played by Alec Baldwin.

Although Norton kept some pieces of Lethem’s plot, he takes the story on his own ride. “Motherless Brooklyn” is about a cat-and-mouse chase engineered by Lionel Essrog, a sweet, orphaned private detective with Tourette’s syndrome who is skillfully played by Norton. In the film, as in the book, Lionel is trying to track down the person who is responsible for the murder of his adored mentor, friend, and employer, Frank Minna, played by Bruce Willis. His search puts him up against Baldwin’s character, one of the most powerful men in New York City. Lethem’s book had no such character.

[Editor's note: When a movie or TV show is set in New York City—and if the people making it are savvy—real estate becomes part of the story itself. In Reel Estate, Brick Underground reality checks the NYC real estate depicted on screen].

Norton isn’t taking any chances that you might not guess which real life person inspired his story’s villain, so he’s named him Moses Randolph. It’s not much of a leap to recognize that this unapologetically ruthless character is modeled on the very real Robert Moses. Though never elected to public office, during his unofficial reign over the city, Moses wielded unwavering power over city officials.

That’s the Robert Moses that Norton shows you in his film. Although Moses had a wide-ranging influence on the entire city of New York and its real estate, Norton focuses primarily on what he did to Brooklyn.

About the real Robert Moses

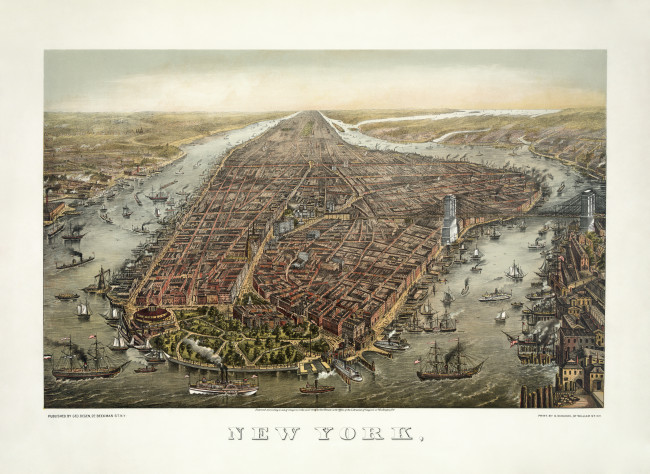

Few would argue about the scale of Moses’ influence. In the course of his decades-long career, Moses ruled the skyline. In his obituary in the New York Times, architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote that he had “played a larger role in shaping the physical environment of New York State than any other figure in the 20th century...His vision of a city of highways and towers...influenced the planning of cities around the nation.”

One reporter wrote in the New Yorker that “In the seven years between 1946 and 1954...no public improvement of any type, no school or sewer, library or pier, hospital or catch basin was built by any city agency unless Moses approved its design and location.”

In what has been considered the definitive biography of Moses, Robert Caro’s 1,300-page Pulitzer Prize-winning “Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York,” the author paints a picture of a complex, almost Shakespearian in character, a seriously flawed but enormously talented man.

Caro’s book details many of the master builder’s transgressions. One of the most egregious, according to Caro, was ordering the removal of what has been estimated to be 250,000 residents from (every borough including Staten island) their neighborhoods, destroying urban areas in favor of a “landscape of red-brick towers” while working “somewhat outside the normal democratic process.”

Although some historians have recently presented revisionist views of the Moses legacy, going a bit easier on him than Caro did in his portrait of the builder; Norton is squarely in Caro’s corner.

Norton’s grandfather—and his real estate roots

That is likely because Norton’s grandfather was James Rouse, a real estate developer and urban planner whose philosophy of city planning was diametrically opposed to Moses’. Rouse was a socially conscious developer, an anomaly among real estate developers of the 50s his time. He wanted to build residential developments with a “strong sense of community...a community which can meet as many as possible of the needs of the people who live there…” He wanted to “feed into the city some of the atmosphere and pace of the small-town village.”

In a recent interview, Norton says that a character played by William Dafoe, a resident of the neighborhood that Randolph wants to tear down, says some of the things that he heard his grandfather say in some of his speeches.

Unlike Rouse, Moses wanted to tear down what he declared as “slums,” and had no problem orchestrating the eviction of anyone who lived in the path of the highways, bridges or unadorned brick towers on his drawing board. No surprise that most of the people whom he exiled were poor, black, and/or immigrants. He built and bullied his way to making New York conform to his vision for a modern city and he had the money to do it. At one point, 25 percent of all U.S. construction dollars were spent in New York City, and as many as 80,000 people were working for him.

Moses never backed down from this “vision.” Just the opposite. In a 1977 television interview, when he was challenged on the subject of “slum clearance,” he says, “Let’s be sensible. How do you visualize the area that we cleared out for the Fordham expansion downtown? They needed the space. Now I ask you, what was that neighborhood? It was a Puerto Rican slum. Do you remember it? Yeah, well I lived there for many years and it was the worst slum in New York. And you want to leave it there?”

What happened in Fort Greene

The heroine of the film, Laura Rose, is a black lawyer/activist, played by Gugu Mbatha-Raw, who works with a community group that is trying to convince Randolph that “a neighborhood is not a slum.” Her group is fighting to prevent Randolph and his band of merry men from tearing down a neighborhood of brownstones in Fort Greene. At one point in the film, Baldwin’s character, who seems apoplectic much of the time, shouts at Lionel, "Power is knowing that you can do whatever you want and not one person can stop you. Those people are invisible. They don't exist."

The film doesn’t say what Randolph had planned for the area after the teardown. If he replicated what Moses did, it could have been to make room for one of his biggest projects, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, which cut the borough’s waterfront off from the rest of South Brooklyn.

Robert Moses revered the automobile. He built a ribbon of highways that cut through and circle the city, including the Grand Central, Interboro and Hudson parkways, the Gowanus Expressway and the West Side Highway. Curiously enough, in spite of his fondness for cars, he never learned to drive. That’s a detail that Norton preserves in the film—Randolph always travels in a chauffeur-driven car.

While Moses’ highway slashed away at some Brooklyn neighborhoods, one neighborhood was conspicuously spared. Whether it was because of the power of a well-organized group of activists or a Robert Moses “head fake” as one Intelligencer blogger thinks, no one can deny that Moses left Brooklyn Heights looking pretty much as it does now. “After all, this was no immigrant ghetto that quaked at the command of City Hall but one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in New York. And while its glory days were well past, Brooklyn Heights in the 1940sstill had real clout—the soft-spoken, old-money clout of club and boardroom.”

East Tremont’s example

East Tremont is another piece of the city that gets a mention in the film. The reference is brief; it comes up at a raucous community meeting where the Fort Greene residents are fighting to avoid the fate of that doomed Bronx neighborhood.

East Tremont, once a primarily Italian neighborhood, was dismantled by Robert Moses to build one of his most despised projects, the Cross Bronx Expressway. The Cross Bronx took 10 years to build and forced the eviction of nearly 4,000 families—they were given just 90 days to vacate their homes. (There were protests, but Moses prevailed in the end.) “There were lots of people who didn’t want to gouge a highway through East Tremont, and they couldn’t stop him,” says Caro, in an New York Times interview.

As one of the characters in the film says about Randolph, “He goes everywhere and tears everything down.” The same could be said about Moses. At least 12 other NYC neighborhoods suffered the same fate as East Tremont; 13 expressways were built throughout the boroughs; 130 miles of concrete was laid, and the lives of more than 250,000 people were changed forever.

Refusing to acknowledge the devastation that his highway would bring, Moses shrugged it off. He said, “There’s very little real hardship in the thing. There’s a little discomfort and even that is greatly exaggerated.”

Moses’ park legacy

Moses’ legacy includes some important projects that were designed to enhance city living. We have Moses to thank for many of our city parks, part of a mind-boggling total of two and a half million acres of parkland that he created in New York state over the course of his career. One of the characters in the film says that the reason Randolph was able to get away with just about anything is because “he built the parks, so they revere him.”

A list of the parks he built or expanded includes Jones Beach (which even Caro calls a “masterpiece”), Alley Park Pond in Queens; Clove Lake Park on Staten Island; East River Park on the Lower East Side; Highbridge Park in Washington Heights and Carl Schurz Park on the Upper East Side. And the Central Park Zoo was his idea.

Many of Moses’ parks had playgrounds, but not many were located in Harlem. One that was had a disturbing feature, according to Caro. Moses liked to “adorn his creations with little details that made them fit into their setting, make people feel at home in them.” Were the trellises at a comfort station in the Harlem section of Riverside Park “decorated with monkeys” in order to make Harlemites feel “at home”? In a recent interview, Caro says that he “understands they’ve been taken down.”

Connecting the city with bridges

Drive across a bridge or into a tunnel in the city and its most likely a bridge or tunnel that Moses put there. He built 13 bridges including the RFK (originally the Triborough), the Bronx Whitestone, the Henry Hudson, the Throgs Neck and the Verrazzano. Even Lionel has to concede, when he meets Moses: “There are some pretty bridges, I’ll give you that.”

Although Moses’ influence on New York’s real estate is all around us, it is interesting to think what the city might look like if some of his projects were never built. A Barron’s article on Moses asks readers to “imagine if Moses had tempered his actions with consideration for the needs of all people, not just those with cars. Picture the Triborough Bridge...with a rail system connecting Manhattan to La Guardia and Kennedy airports...When Moses gained power in 1924, NYC had one of the world’s most modern subway systems.” In 1968, at the end of his career, “it had one of the worst-maintained systems.”

Cooling the city with swimming pools

Moses loved to swim, and Randolph loves to swim too, and in the film there are several shots of him in a swimming pool or sitting on a bench alongside one.

Moses was a huge fan of public swimming pools. He told the New York Times that “it is an undeniable fact that adequate opportunities for summer bathing constitute a vital recreational need of the city’s residents.”

He made the summer of 1936 the summer of the swimming pool. Every week another swimming pool opened across the city, to enormous fanfare. Bojangles performed at the opening of the Jackie Robinson pool in Harlem (then called the Colonial Park Pool); the opening of the Red Hook pool attracted 40,000 people; and 75,000 were on hand for the opening of the McCarrenpool in Greenpoint.

When that summer was over, 11 pools had been opened, which the Landmarks Preservation Commission describes as “among the most remarkable facilities ever constructed in the country.”

A modern Robert Moses?

Some historians think that New York needs a new master builder, another Robert Moses for the 21st century. Caro disagrees: “We don’t need a new Robert Moses because he ignored the values of New York. If anything, I see the city moving today to correct his ravages.”

Norton’s portrayal of an individual endowed with so much raw power over the buildings, streets, bridges, tunnels and roadways of the city underscores how dangerous another Robert Moses would be.

You Might Also Like