Joanna Scutts, author of "The Extra Woman," on 1930s NYC, female independence, and Marjorie Hillis' groundbreaking philosophy

Joanna Scutts

Liveright

Joanna Scutts is a native Londoner, longtime New Yorker, and a writer, historian, and literary critic. She's also the postdoctoral fellow of women's history at the New-York Historical Society and author of The Extra Woman, an exploration of the life and legacy of a pioneering New Yorker named Marjorie Hillis.

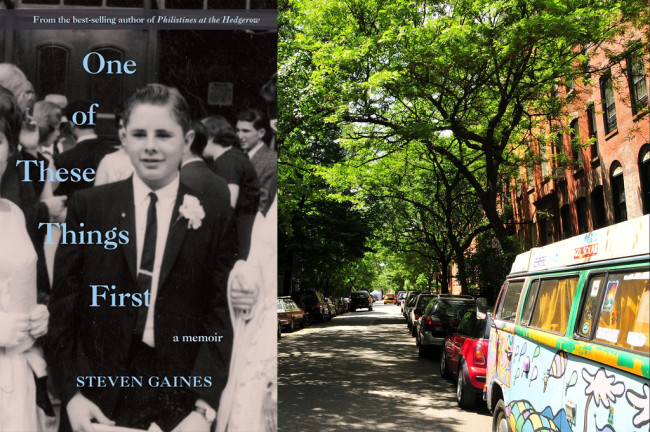

Hillis grew up in Brooklyn Heights, the daughter of a preacher. These are perhaps not the origins one would imagine for a woman who went on to edit for Vogue and write groundbreaking books about the rewards and pleasures of the single life. But in 1936, she published Live Alone and Like It: A Guide for the Extra Woman, a self-help book that celebrated female independence in the midst of the Great Depression. At the time single-dom was synonymous with spinsterhood, not to mention financial precariousness.

In The Extra Woman, Scutts covers Hillis' life and career—she went on to write several more books after her guide for "live-aloners" became a smash hit—as well as the broader cultural landscape she operated in, and left her mark on.

We spoke to Scutts about 1930s New York, what singles today can learn from Marjorie Hillis, and her own experiences navigating the city.

How did you discover Marjorie Hillis? What fascinated you about her?

I stumbled across her through getting a copy of the book from a friend. I had no idea she was a New Yorker—I was living in NYC at the time but I'm originally from London. A friend gave me a copy from 1936 that she had found, and I later discovered it was the British "translation" of the American original. It had been a huge hit in the summer of 1936 in the U.S., this guide to being a glamorous "live-aloner." They later brought out an edition in the U.K., but instead of just changing the spelling, they changed a lot of the references, too. All of the sights and sounds of London stood in for the sights and sounds of New York. I was like, "Who is this fabulous unknown British writer from the 30s?"

I later found out she wasn't actually British–she was from Brooklyn. She was born in the Midwest and then in 1899, her father became head of Plymouth Church [in Brooklyn Heights]. They lived on the river a few blocks down from the church in that historic neighborhood. Later, she moved to Manhattan when she was grown and independent and a working woman.

What role did New York play in Marjorie's philosophy?

After her parents died, she had a near miss with the suburbs. Her brother was in Bronxville and was married and had four children, and after her father got sick, the family moved up there. She writes about being the only woman waiting with the commuters going down to Grand Central on the Metro-North. She hated that lifestyle. She was terrified of becoming the maiden aunt around the corner.

After her parents passed away, she moved to Tudor City, which was down the road from the Condé Nast offices. She worked at Vogue at the time, which was in the Graybar building next to Grand Central. She could go home for lunch and walk back to the office.

Tudor City was a fairly new development then, a new idea in city living. They made it appealing to women and young professional families. There were all kinds of amenities on the site, parks and gardens and nurses on call to take care of you when you got sick. There were restaurants, and you could get takeout delivered to your door. When I read the advertising materials, I was like, "I want to live in Tudor City!"

The development tried to stand in for the family and community you might not have around you, and the ads from that period show you that you can enjoy city life to the fullest there. Marjorie loved going to the theater, and at the time, if you were trying to catch the train back to the suburbs, you missed the end of the play. The convenience of places like Tudor City allowed you to take part in the life of the city. That was really important to her. Part of her philosophy was that to be successful at living alone, you had to cultivate your interests, and you had to position yourself to do that.

What was New York like for women in the 1930s, when Hillis's book was published?

Marjorie belonged to and was writing for an elite readership. She wrote for working women, but not for those really struggling during the Great Depression. For those women, the last thing they were concerned about was making the last act of the play. But things were definitely changing. There were a lot more women working than before. White collar jobs were opening up to young women. There was still the cultural expectation that you do this until you're married, but women were entering public life and public spaces in a way that they hadn't in previous generations.

High society in NYC was still very worried about too many women, especially groups of women together. People didn't want a "hen party," and the doormen at elite clubs like the Stork Club would be really strict. They wanted women to have dates. Marjorie thought it was a great idea that this entrepreneurial salesman at the New York Times got underemployed, educated young men to be hirable by the evening by rich women who wanted to go out. The women would give them cash and they would pay for everything with it to make it seem like the men were still in control. This thrived for a couple years, until the entrepreneur behind it was shut down by the city in 1939.

How important was having a room of one's own to making it work as a live-aloner?

It was pretty important. She was certainly dealing with a world in which it felt more possible to do that. Her view of the economics of this situation was fairly breezy: She wrote if you care about nightlife and living in fashionable neighborhood, you may need to get a smaller place. Or if you're kind of messy and need more space, live further out and get a bigger apartment.

She gave the impression that real estate was a question of pounding streets until you found the perfect space, and living further out was better than living with roommates or family. She believed it was important to have room to yourself so you could control your space, and advised having people over to make sure you weren't lonely. We're much more used to this idea now.

What do you think Marjorie would make of the city today, especially given how difficult it is now for a single person to afford her own place here?

I get the sense she would embrace forward-thinking ideas like micro-apartments. She'd be excited about Citi Bike for how it opens up the city. All these ideas that don't help the larger situation but put values she appreciated up front, like being independent and having a place of your own.

She saw even then that there's a trade-off between a neighborhood that's hip and convenient and a neighborhood where apartments are affordable. For her, she would've said, Go as far out as you can and still be in New York City. She might have had a little more faith that the subway would work!

I definitely think she was one of those New York exceptionalists. Moving to Pittsburgh would not have been a solution for her. The city for her was Manhattan. When she grew up in Brooklyn Heights, it was more of a stodgy, suburban place. She'd be amazed at Brooklyn becoming a viable part of the city.

What parallels do you see between Marjorie's approach to the single life and the lives of single women in New York today?

Attitudes around single women have changed a lot. It's more common now that young professional women in the kind of privileged groups that she belonged to and was speaking to have other single friends and are single longer. She suggested that you have to cultivate those friendships, but once they're married, you won't see them again. But that attitude that you can't be friends with married people, or you can't have an uneven number of people at dinner parties—those norms have shifted.

There's still that expectation of explaining to family why you're not married, though. It can still be a challenge to say, "I don't lack anything because I'm single. Other things in my life fulfill me and make me happy." It's still very hard for people who are married and have families to accept that that can be true. Those attitudes linger.

A lot of her book is quaint, but a lot about her philosophy still resonates, especially the notion that your happiness up to you, and you're not going be happy single if you see yourself as lacking something. You have to conquer envy and find what makes you happy.

How long have you lived in New York? Which neighborhoods have you lived in?

Almost 15 years. I didn't move as much as most people do. I've lived in three places and one of those was only for five months. I first lived in Columbia University housing when I arrived for my PhD. I lived in two different apartments in Morningside Heights, always with a roommate up there. Then I moved in with a friend at the end of my program, right around the time of the financial crisis, which opened this brief window when apartments in neighborhoods that had been totally out of reach were available again.

I moved into a room in an apartment my friend had been living in for a while in Williamsburg on South Second Street, which was then very uncharted. Even in the five months I lived there, I was seeing the bars and restaurants creeping down Bedford, getting closer to where we were.

I met [my husband] Tony right when I started living there, and then the lease was up for renewal in October. Romances are accelerated by real estate in New York. I basically said to him, "So, you live in a rent stabilized one bedroom in Astoria all by yourself—how about it?" We'd been dating for five months so it was definitely fast, but we knew it was going to stick. I'm still here and I love this place. I'm very lucky.

How does the city inspire your own work?

All New Yorkers become historians of the city. People who love it absorb that history. There's a Colson Whitehead essay about how when you live in New York for any length of time, you become a city archaeologist. You remember when that laundromat was a barber shop. Everyone has their own history and picture of the layers of the city. You build that up really fast. Urban history and the history of urban planning become a side obsession of mine. Growing up in London, I was always fascinated by cities and how they change.

It's simultaneously frustrating and exhilarating. I get uncomfortable in places with quiet and trees. I don't trust that landscape in the way I trust Broadway.

You Might Also Like