When a homeless shelter comes to the neighborhood—and neighbors hit the roof

In an ever-changing (ever-gentrifying?) city, it's no surprise that NIMBY-ism—as in "not in my backyard"—is alive and well. And in NYC, it seems to be everywhere lately. Recently, residents of Maspeth, Queens have taken to the streets to protest a proposal to convert a local Holiday Inn to a 110-bed facility for the homeless, reports the New York Daily News. The shelter was expected to open on October 1, but as of now, the conversion has been delayed.

Robert Holden, president of the Maspeth and Middle Village neighborhood group Juniper Park Civic Association, says that community members have heard conflicting reports about the status of the shelter plan. What they do know—and what concerns them—is the type of shelter that will be put in place should the proposal go through.

“It will be a full-blown shelter with metal detectors, DHS police, security on every floor,” Holden says. “What they’re doing with these shelters is turning a viable hotel into a jail without bars. They’re using our neighborhood as a prison yard.”

The Maspeth shelter would bring in 220 new residents, Holden says, which would include those with mental illness and drug addictions, as well as former prison inmates. “It’s a known fact that crime goes up [when you bring in a shelter],” Holden adds. “We’re getting a certain population that is not good for the neighborhood.”

But as Catherine Trapani, executive director of Homeless Services United, points out, "mentally ill people are more likely to be the victim of a crime than the perpertrator." Moreover, she adds, "there's no evidence of a crime increase resulting from shelters coming in. Some neighborhoods, like the East Village or the Upper West Side, have many shelters, and you wouldn't think of those as depressed or high crime areas."

According to Holden, a coalition is now forming between residents of Maspeth and other areas where shelters are going up, including Sunset Park, Long Island City, and the Bronx. But as with anything revolving around housing, the issue is complicated.

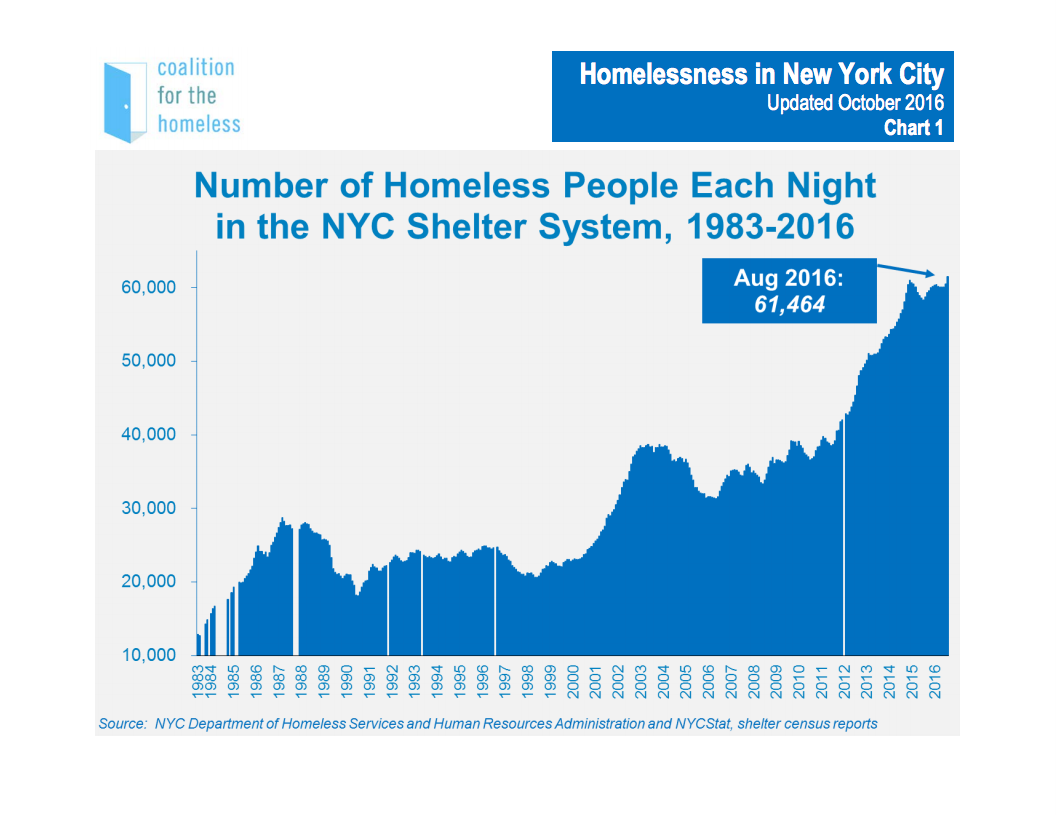

First, some background: As of August 2016, the number of homeless New Yorkers has spiked past 60,000—the highest level since the Great Depression, according to Coalition for the Homeless, the oldest advocacy organization of its kind in the nation.

And as the Department of Homeless Services explains, homeless people have a mandated "right to shelter," which means that every man, woman, and child without a place to live is eligible for emergency shelter and services each night. To fulfill its legal obligation, then, the city must build apartments to serve the need—but when a new shelter is planned for their neighborhood, many New Yorkers push back, citing quality of life concerns.

Advocates for the homeless insist that what’s really needed is more compassion and tolerance for the city’s homeless population—as well as action from political representatives at the city, state, and federal levels to improve access to affordable housing.

Why has the homeless population increased?

The number of homeless New Yorkers has skyrocketed in recent years (see the graphic below). According to Joshua Goldfein, an attorney with the Legal Aid Society’s Homeless Rights Project, much of the blame falls on the shoulders of state government.

"The governor has stonewalled the city on providing the right subsidies for supportive housing for people to move out, and as a result, the city is left holding the bag.” Goldfein explains. (The Department of Health defines supportive housing as “a combination of affordable housing and support services designed to help individuals and families use housing as a platform for health and recovery following a period of homelessness, hospitalization or incarceration or for youth aging out of foster care.”) “Much like the current mayor, the previous one got into a tiff with the governor, who in retaliation eliminated part of the funding for housing subsidies. Bloomberg then cut it off altogether.”

In 2011, per an article in the Gotham Gazette, Governor Cuomo and Mayor Bloomberg ended a program called Advantage, a rental assistance program that used subsidies to help homeless families transition into affordable housing. By 2014, the number of homeless in NYC had shot up by the thousands. Goldfein says consequently, as Mayor De Blasio tries to address the crisis, he must also contend with landlords who are furious that the city stopped paying subsidies, not to mention an increasingly pricey housing market.

Giselle Routhier, policy director of Coalition for the Homeless, says that another source of the problem is at the national level. “The federal government needs to stop disinvesting in housing resources like Section 8,” she says.

Moreover, she adds, there’s a misallocation of resources within NYCHA, the city agency that provides affordable housing to low and moderate-income New Yorkers: “There are still resources in NYCHA going to people with no demonstrated housing needs," Routhier says. One such example of this was outlined in a report from Gothamist, which explained how some residents of Hasidic communities successfully apply for Section 8 vouchers in bulk with the assistance of local organizations; meanwhile, 120,000 people remain on the Section 8 waitlist.

Trapani says the real problem is that housing costs have risen while pay has not: "Wages have stagnated and rental housing keeps going up. Subsidies helped bridge that gap, but Advantage ending created an influx of people back into system, and also made it harder for folks to exit."

Holden, on the other hand, argues that the city has made it too easy for people to get free housing, enticing the homeless from outside New York. He notes that under Mayors Giuliani and Bloomberg, the city used to fly the homeless people who arrived in New York from elsewhere back to their city of origin with free one-way tickets.

“When De Blasio came in, he said, ‘That’s inhumane, we're not sending them back, we're going to take them,’” Holden says. “That’s the reason for the homeless shelter increase. Taxpayers are paying for this and De Blasio has no plan to make this better. “

Trapani says that actually, this practice is still in place, and for some homeless people, it's a good solution. "Part of what they do when you apply for shelter is they talk to you and ask if you can go somewhere else, if you have family somewhere who can take you in," she explains. In some cases, a homeless individual might have a relative they could live with in another part of the country, but be unable to get there, so the city steps in and pays for their travel. "That costs the city too, but it's cheaper than paying for someone's shelter stay," Trapani says.

How does the city decide where to place shelters?

“The city will not tell us how many homeless people are in Maspeth,” Holden says. “We’ll accept our Maspeth homeless, but not 220 people from other areas.”

But that’s exactly what neighborhoods across New York must do, Goldfein says: “If the city finds a space they will try to use it. It’s not like they have a choice between Maspeth versus Park Slope. That’s where the building is and they need to use it or they’re going to be in violation of the law. They do not single out any community.”

However, Goldfein notes that, while not by design, there are often more homeless shelters in low-income communities than in wealthy ones. “The kind of place where you’re going to be able to put in a shelter is a place where the shelter operator is competitive in the market, where rents are low and there isn’t a lot of competition for that use of property,” he explains.

The conversion of hotels to shelters seems particularly indicative of how urgently the city needs housing for the homeless: The hotels are often used as temporary accommodations when supportive housing is unavailable. In June, Vice wrote about several of the 41 such shelters in the city; reporter John Surico found that the residents were grateful for their temporary lodgings, but also eager to find something more stable.

“Does anybody think putting the homeless in hotels is a solution?” Holden asks. “It’s a recipe for disaster.” He points out that shelter conversions displace hotel workers, which could, ironically, even force them into the shelter system themselves.

Trapani says the reliance on hotel shelters has to do with their immediate availabilty. The city doesn't want to take affordable housing offline by converting it to shelters, and the ideal scenario--purpose-built shelters designed specifically with the homeless population in mind--is very time-consuming. "The right to shelter means whenever someone is in need of a place to go, the city needs to furnish it right away," she says. "Hotels are right away."

How does a shelter impact the community?

Holden says that the city tells communities like Maspeth that they are obligated to do their fair share in taking on facilities for the homeless, but fails to hold up its end of the bargain when it comes to security. “Normally, security for the shelters is provided by private security firms or in conjunction with the DHS,” Holden says, “but it's gotten so bad that they have to call in the NYPD now to up the security.”

He mentions that the police have been called multiple times to one of the hotels that Vice visited, and indeed, the article notes that within a number of days, one resident assaulted her roommate, another broke the facility’s metal detector, and others were accused of robbing a pharmacy.

Goldfein says that rather than reduce the quality of life in a neighborhood, though, a homeless shelter can actually bolster both safety and commerce: “My impression is that it improves the neighborhood, because a lot of people are coming who are getting services and spending money. It makes people safer when there’s more activity. And many shelters are run by not-for-profits that are solid corporate citizens of New York. They want to improve the community where they are, so you’ve got a new partner.”

Plus, Routhier points out that there’s a moral component to accepting the presence of a new homeless shelter. “We’ve seen other instances that with the vitriol that gets thrown out, kids start getting bullied at school because of it. The negative effects are very disturbing.”

One Brick Underground writer recounted her experience living on the same block as an SRO, a single-room occupancy building typically home to low-income and formerly homeless New Yorkers. Initially, the property was a source of drug and prostitution-related crime, but when neighbors created a block association and helped a more reputable organization take over the building’s management, conditions improved tremendously. “…for the most part,” she wrote, “our SRO neighbors are just that, neighbors."

It’s key to rememember that the residents of a homeless shelter in your community are your neighbors, Routhier advises: “We don’t have to be afraid of our neighbors. When you’re welcoming, it’s easier for the community and for homeless individuals to adjust. The more welcoming you can be, the better it is for everyone.”

You Might Also Like