What to know about the ongoing discriminatory practice of redlining in NYC

Racism in lending practices has had a lasting effect on the development of historically poorer neighborhoods in NYC.

FrankvandenBergh/iStock

Amid the furor over the killing of George Floyd, which has sparked widespread protests in support of Black Lives Matter across the U.S. and New York City, the concept of systemic racism is getting new attention. You may have seen on social media a child-friendly video created 2019 by Alex Cequea that explains the historical roots behind the differences between Jamal, an African American boy who lives in a poor neighborhood, and his white friend Kevin, who lives in a wealthy neighborhood.

The children grow up with disparate opportunities, even though they live only blocks apart, because government agencies historically mapped U.S. neighborhoods, designating them as desirable or undesirable for investment, creating lasting disparity.

Getting financing to buy a house or apartment is a crucial step in the process towards home ownership, and blocking access to funds has historically been used to prevent people of color from owning property. Bias in lending is not just a thing of the past: New studies have found evidence of racial discrimination by banks against home loan applicants in dozens of cities.

Bias among real estate brokers also creates segregated neighborhoods. A bombshell, three-year investigative report by Newsday last year found that almost half of all black homebuyers and renters on Long Island are likely to face discrimination from real estate agents and brokers. The report found that some agents showed minorities fewer listings or scrutinized their finances more heavily. White buyers often received coded messages designed to steer them away from minority communities.

[Editor's note: An earlier version of this post was published in March 2019. We are presenting it again with updated information for June 2020.]

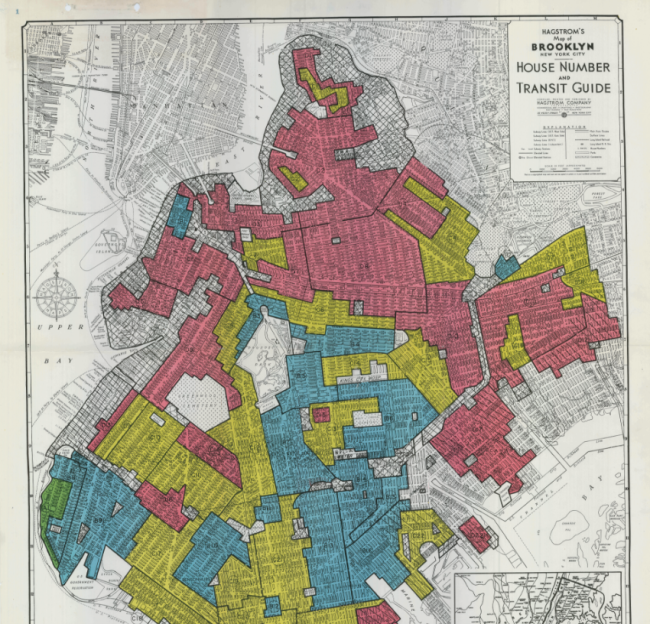

The exclusionary practice of mapping neighborhoods is called redlining, and refers to 1930s maps used by banks to determine who they’d lend to—African American neighborhoods were highlighted in red and deemed "hazardous," which meant residents there didn't qualify for loans.

Financing is of course a significant consideration in NYC. The median sales price for an apartment in Manhattan hovers around $1 million. To get a sense of how hard it is for most New Yorkers to get a down payment together, the median household income based on U.S. Census data is $57,782.

In 2019, the Center for Investigative Reporting, along with Reveal, WNYC's in-depth news program, published details of modern day redlining in 61 metro areas from Oklahoma to Florida and as close to home as New Jersey. They didn’t find clear evidence of discrimination in New York City but the New Economy Project used the same methodology and found banks and other mortgage lenders were significantly more likely to deny loan applications as the percentage of black or Latino residents in New York City neighborhoods increased.

Parts of Brooklyn, Queens, the Lower East Side, and Harlem lost opportunities for investment due to redlining. It's no surprise redlining maps had an "economically meaningful and lasting effect on the development of urban neighborhoods through reduced credit access and subsequent disinvestment." That's the verdict of an updated study by The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

The persistence of bank redlining in NYC is troubling enough but the New Economy Project claims it "lies at the very heart of neighborhood segregation, inequality, and poverty." Their research found banks and other mortgage lenders denied black applicants more than twice as often as white applicants, by 26 percent over 12 percent. They also identified similar denial rate disparities for New Yorkers looking to refinance an existing mortgage, identifying that banks and other lenders denied 53 percent of black, 44 percent of Latino, and 40 percent of Asian New Yorkers, compared to 30 percent of white New Yorkers.

The Community Reinvestment Act (1977) was an attempt to redress inequity by making sure banks served poor neighborhoods and faced consequences if they didn’t. The New Economy Project says entrenched patterns of bank redlining indicates "these laws have proven woefully inadequate." Cut to the current administration—following a pattern of deregulation, the government has asked for public comments on ways to modernize the rules.

That has critics worried it will make it easier for banks to tick the box of compliance rather than actually provide the loans they should. In an open letter, the New Economy Project suggests the focus should be on "assessing whether national banks are equitably meeting community credit needs" rather than prioritizing how convenient it is for national banks to meet certain guidelines.

If you are concerned you are being denied a loan based on your race, the best starting point is to contact the Fair Housing Justice Center.