Here's what you need to know about sponsor units—and how to find one

Morningside Heights one-bedroom, one-bath co-op, $749,000: This renovated sponsor unit at 535 West 110th St., between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue, has high ceilings, a windowed kitchen, a windowed pantry and a new bathroom. The apartment is located in a prewar co-op building with a 24-hour doorman, a resident super, a laundry room, a bike room, storage bins (for an added fee), a gym, and a two landscaped roof decks.

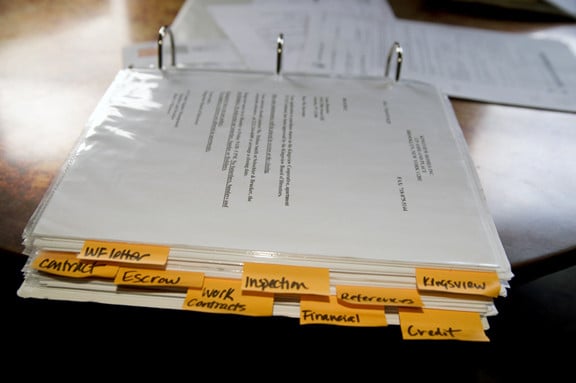

Sponsor apartments are among the most sought-after co-ops on the market today, mostly due to the fact that buying one allows you to skip the dreaded board interview process, which can trip up even the most qualified of applicants. Jillian Finn of Bond New York and Nicole Gary of Keller Williams Tribeca tell you what you need to do in order to score one for yourself in this week’s Buy Curious.

The proposition

I'd like to buy a sponsor co-op and avoid dealing with the board. How do I go about finding one?

The reality

First thing's first: we should probably explain what exactly a sponsor unit is.

“A sponsor unit is a unit owned by the original owner or corporation responsible for turning a building from a rental into a co-op or condo,” Gary says. During the process, some apartments are kept as investments by the developer (or "sponsor") of the conversion.

Why would you want one?

The main reason is simple. Buying a sponsor unit means that prospective purchasers can dodge the entire board application process, which can be arduous and stressful.

“When you purchase from a sponsor you do not have to submit a board application or go for an interview,” Gary says. “It saves a lot of time, and the buyer does not have to worry about getting denied.”

Finn adds, “Co-op boards are not required to give a reason for any rejection, and depending on the board, [this] can be a very invasive process. This is a huge reason why it is attractive for a buyer to buy a sponsor unit.”

(With condo sponsor units, “there really is no big draw per se,” Finn says. “It really isn’t such a big deal in condos.”)

Since there are fewer hurdles to clear for co-op sponsor units, closings can also be faster than usual.

Plus, you might be able to get away with a lower down payment. A typical down payment on a non-sponsor co-op can be anywhere from 20 to 35 percent. But if a sponsor is okay with getting less money at the outset, a buyer might be able to put less money down. This practice "is very common, actually," Finn says, adding, “In a sponsor co-op unit, the developer can accept a down payment as low as 10 percent.”

How common are they?

In a few words, not very.

“They are much less common than a resale of a co-op or condo,” Finn says.

“They only come on the market when a lease is up and the sponsor decides they want to sell versus keeping the unit and continuously being a landlord,” Gary says.

How do you find one?

It’ll take some legwork, Gary says, although many real estate search sites—StreetEasy, for example—offer the option of searching for sponsor units specifically.

“When I have a client looking for a sponsor unit, I contact all of the sponsors I know to see if they are willing to sell,” Gary says. “In addition, I contact other brokers who I know have relationships with sponsors to see if they have any inventory that is not yet on the market.”

Finn says that luck also plays a big part in finding a sponsor unit, but that hitting the streets and the phones heightens your chances.

“Speak to neighbors, community groups, schools boards, etc.,” she says.

Where should you look for one?

Sponsor units can be found all over New York City, according to our experts. One place to look is the prewar buildings that are plentiful on the Upper East and Upper West Sides.

Are there any disadvantages to buying a sponsor unit?

“There are more out-of-pocket costs for buyers when purchasing a sponsor unit,” Gary says, explaining that the buyer is responsible for paying both New York state and New York City transfer taxes.

New York state transfer taxes are computed as $2 for every $500 of the purchase price, and New York City transfer taxes are computed as one percent of the purchase price for a purchase price up to $500,000, and 1.425 percent for a purchase price greater than $500,000.

Gary adds that “there is sometimes a flip tax, as well, which is usually 1 to 3 percent, depending on the building.”

The buyer is also sometimes responsible for the sponsor’s attorney fees as well, she says.

What condition are the units usually in?

It varies. According to Gary, “usually sponsors fix up and renovate [the units] prior to putting them on the market for sale, so they are in newly renovated condition. Sometimes, however, they are in original condition and need a gut renovation.”

In Finn’s experience, buying a sponsor unit means you’re more likely to get a fixer-upper.

“Sponsor units in co-ops are usually kept for the sole purpose of investment and income property,” she says. “There’s not a great personal interest in the unit… and some investors aren’t interested in the headaches that come with renovations.” If that’s the case, you’ll have to factor in the money you’ll need to spend to fix the place up.

Are sponsor units typically more or less expensive than other units?

“In my experience, they tend to sell for a little more,” says appraiser Jonathan Miller of the firm Miller Samuel. “They are often renovated and have favorable terms that don’t apply to others. Those favorable terms aren’t consistent across all listings, but they… bypass board approval and allow lower down payments. As a result, these apartments tend to be a little more expensive.”

Finn agrees, saying, “There are many variables, [but] they can be more expensive because of the attractiveness of no board approval and a swift closing.”

Curiosity piqued? Here are some sponsor unit co-ops that are on the market now:

Midtown East studio, $395,000: This gut-renovated studio at 5 Tudor City Pl., between East 40th and East 41st streets, has a modern kitchen with gray cabinets, a dishwasher, and a two-burner cooktop. There's also a bathroom with marble flooring and a marble vanity. The full-service prewar building has a 24-hour doorman, a full-time super, maintenance staff, concierge services, a laundry room, and a fitness center (for an additional $39 a month).

Lenox Hill studio, $525,000: Located at 301 East 69th St., between First and Second avenues, this east-facing studio has three closets, a separate dressing area, upgraded electrical, a renovated kitchen with stainless steel appliances and Caesarstone countertops, and a newly tiled bathroom with a new vanity. In a full-service luxury building.

East Village two bedroom, one bath, $895,000: This renovated second-floor apartment at 321 East 12th St., between First and Second avenues, has a windowed kitchen with stainless steel appliances and a windowed bathroom with a marble-tiled shower. The pet-friendly building has a live-in super, a bike room, and storage space.

Gramercy Park three bedroom, two bath, $1,995,000: This prewar combined unit at 242 East 19th St., between Second and Third avenues, offers high, beamed ceilings, refinished hardwood oak floors, a large west-facing living room with a wood-burning fireplace, and a separate dining area. The art deco building is pet-friendly, and has a 24-hour doorman, a live-in super, bike and common storage, a landscaped rooftop garden, and a laundry room.

Chelsea two bedroom, two bath, $1,595,000: Located at 130 West 16th St., between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, this two bedroom has, according to the listing, white oak floors, exposed brick and nine-foot ceilings. Located in a pet-friendly elevator building with a bike room and a live-in super.

You Might Also Like